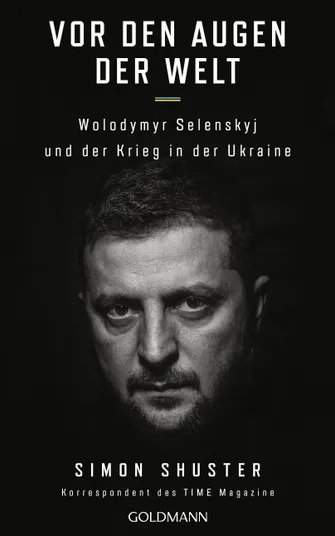

Simon Shuster had access to the Ukrainian president like no other. Read exclusively the first chapter of “The Showman” here. How Volodymyr Zelensky experienced day one of the Russian invasion.

01/20/2024

The US journalist Simon Shuster has been reporting on Russia and Ukraine for 15 years, mostly for Time magazine. Born in Moscow, he emigrated to the USA as a child. Shuster already knows Volodymyr Selenskyj from his time as a comedian and actor. Over the years he has accompanied and portrayed the Ukrainian president. For his research, Zelensky gave the journalist more open access than anyone else. No one in the presidential administration – neither Zelensky nor his advisers – kept a diary. “They were too busy with the war,” says Shuster. He wrote a biography based on his observations.

“It started — let’s kick them in their buts!”

Volodymyr Zelensky did not feel particularly attached to the estate he left at the start of the invasion. For almost a year and a half, it had been a pleasant place for him and his family to live, with a separate living quarters for their bodyguards and a large plot of land for the dogs to run until they were tired. But the house itself – with a neoclassical façade made of yellow stone, located on plot number 29 in the gated Koncha-Saspa residential complex – seemed excessively ostentatious, almost ostentatious, to the former comedian. In a word, it was too presidential for Zelensky.

As a man who had spent his entire life acting and was able to change roles as quickly as his stagehands could rearrange the sets for the next skit, Zelensky disliked the large and regal role of President. She didn’t fit the character he had cultivated for decades on screen and on stage: the grinning joker, the tireless charmer, the patter on the back who believed that everything would be okay in the world in the end. Standing just under 5 feet 7 inches tall with sparkling eyes that bulged slightly beneath his dark, expressive eyebrows, Zelensky’s success both as a comedian and in politics rested on his ability to pull off a role, to appear believable and normal like someone from next door.

Millions of people in Ukraine had watched this figure mature over the years into the greatest satirist of his generation, able to win over any audience with his wit by nailing politicians to the wall. When it came to preserving this image, he did himself no favors by choosing the residence in Koncha-Saspa. It was built for politicians, not political comedians, and the president struggled to call it home. “For me it’s like a hotel, otherwise I wouldn’t use it,” he said apologetically after his family moved there in the summer of 2020.

The press never forgave him. Until the day he became virtually immune to criticism as a wartime president, journalists were fond of reminding Zelensky of the most famous lines he had ever uttered in his television career. In the key scene of his most successful sitcom, which also paved his way to the presidency, Zelenskyj’s character, a history teacher, complains about the greed of the political elites and especially about their magnificent houses:

“These motherfuckers come to power and all they do is steal and talk shit, talk shit and steal. Let a simple teacher live like a president, and let the shitty president live like a teacher.”

This speech, first broadcast in Ukraine in 2015, was the birth cry of Zelensky’s political career. She got him into office and then persecuted him. It also provides an explanation for why he was not a popular leader in the third winter of his presidency, when Russian troops surrounded Ukraine in the north, east and south. He was a frustrated head of state who had promised peace and failed to keep that promise. He was the joker who thought he could run a country of forty-four million people the way he ran his film studio. He was the reformer who promised to drive politicians out of their villas and let them cycle to work. However, on that terrible night when the residents of Koncha-Saspa were awakened by the sound of Russian bombs, Zelensky himself was sitting in a villa, bathed in the soft light of a chandelier.

At around 4:30 a.m. on the morning of February 24, 2022, the disturbance reached the president’s bedroom, where First Lady Olena Selenska was still sleeping. It took a few moments before she noticed the deep blasts coming through the windows. At first they sounded like fireworks. Then she opened her eyes and saw in the darkness that her husband’s side of the bed was empty. The president was standing in the next room, getting ready to go to work, already wearing a dark gray suit. When she found him there, the confused look on his face prompted Zelensky to say a word to her in Russian, the language they spoke most at home. Natschalos, he said. “It has begun.”

She understood what he meant. The news in Ukraine has been warning of an impending war for months. Talk shows debated which officials and lawmakers were most likely to flee. One program gave advice on what to pack in an emergency kit before setting out as a refugee. Some of the direst predictions came from Ukraine’s Western allies, particularly the U.S. intelligence community, which had concluded that Russia was planning an invasion from three directions and would likely overrun the capital within days. It was said that the Russians’ goal was to take over most of the country and depose the Zelensky government.

To many Ukrainians, these predictions had sounded absurd. The attack, if it came, was not expected to extend beyond the border regions to the east. For about eight years, Ukraine and Russia have been engaged in a protracted war over two separatist areas in eastern Ukraine. Few in Kyiv believed the recent escalation would extend too far beyond these regions. Even fewer believed she would ever reach her homeland. Until the last few hours, Zelenskyj didn’t believe in it either. He did not tell his wife to prepare. It was only on the eve of the invasion that the First Lady made a note to pack a suitcase or at least gather the family’s passports and other documents. But she didn’t get around to it. The day, as so often happens, went by far too quickly with routine tasks and errands. She did a few things and did homework with the children. Then they had dinner and watched TV.

The president didn’t come home until well after midnight and said nothing that would have suggested to his wife that they were in danger. That night they went to bed without making any plans for war and slept only a few hours before the bombing began. Now the First Lady could see from his eyes that the situation was much worse than she had imagined. “Emotionally he was like a guitar string,” she said later.

“His nerves were strained to breaking point.” Yet she remembered no confusion or fear in his expression. “He was completely composed and focused.” Apparently so focused that he didn’t even wake up his children and say goodbye to them. He just asked his wife to tell them what happened. He promised to call her later and give her instructions on what to do next. “We were still processing what had happened,” she said. “We never thought something like this could happen, because all the talk about the war was just talk.” The sound of the explosions outside had catapulted them into a new reality.

Outside, the president jumped down the few steps to the driveway and climbed into a vehicle in his waiting motorcade. The metal gate opened and its driver turned north onto the tree-lined road through Koncha-Saspa. Meanwhile, Zelensky passed the familiar scenery of his commute on the E40, the soccer field to his right, a gold-domed chapel to his left, the billboards advertising condominiums at every exit. It was the last time for many months that he saw it all in a peaceful state, with intact bridges, no military checkpoints, no anti-tank barriers and twisted metal in the streets. In a day or two Kyiv would once again resemble a fortress and return to the state of siege that had defined much of its history. For a millennium and a half, European empires had fought over this ancient city on the banks of the Dnieper. The Vikings, the Ottomans, the Mongols, the Lithuanians and the Poles had laid claim to Kyiv, its centers of trade and knowledge, its monasteries and cathedrals. The Russians first sacked the city in the 12th century. Now they tried again.

In the back seat of the car, Zelensky sat silently, looking at his phone. As the motorcade sped through the darkness, a flood of calls and messages poured in. One of the first callers was his friend Denys Monastyrskyj, the interior minister responsible for state police and border protection. He was a few years younger than Zelensky, but looked older and tougher and a bit like a prizefighter. For the past three days, Monastyrskyi had been sleeping in his office at the Interior Ministry, waiting for signs of the Russian attack, and now it was his job to inform the president that the attack had begun. Zelensky asked him where exactly. He wanted to know which direction the Kremlin had chosen to attack.

“Everyone,” said Monastyrsky. Enemy forces bombarded Ukrainian positions along the entire eastern and northern border with artillery, multiple rocket launchers and aerial bombs. Russian fighter jets flew over major cities to eliminate Ukrainian air defenses and capture the airspace. There was silence on the line. The president needed a moment to process the information. Then he said a sentence that Monastyrskyi would remember for a long time: “Fight them back.”

Such confidence, even in the face of grave danger, had always been one of Zelensky’s strengths. At that moment, however, she seemed out of place and bordered on megalomaniac. He knew that Ukraine lacked the means to repel the Russians. At best they could be held off for a few days, hopefully long enough for the military and political leadership to orient themselves, mobilize resources and save the parts of the country that would not be overrun in the first wave of attacks. Due to his behavior before the invasion, Zelensky was at least partly to blame for the poor state of the national defense. For weeks he had downplayed the risk of a full-scale invasion and assured his people that everything would go well. He had rejected the advice of his military commanders to call up all available reserves and use them to reinforce the border. In addition to the catastrophe of the invasion itself, the president also had to deal with his own failure to have foreseen it. But there was time for that later.

The car headed for his office on Bankova Street, although it wasn’t the safest place for him. The presidential office is in the middle of a densely built-up neighborhood, surrounded by apartment buildings, bustling cafes and cobblestone streets lined with boutiques. The nearest apartments were close enough to Zelensky’s office that someone could throw a grenade through the window. When he arrived around 5:00 a.m., the streets were unusually busy at that time of day. People prepared to flee, bringing their suitcases and pets outside and strapping their children into car seats. Zelensky’s bodyguards did not know whether Russian saboteurs had loaded one of the cars parked on the side of the road with explosives. His residence in Koncha-Saspa had at least a security fence and a metal gate. There were no such security measures at the presidential office compound in central Kyiv, but Zelensky insisted on going there first. It was the seat of presidential power, and his message to the senior advisers and ministers who called or texted him that morning was the same: Go to the office. I’ll wait for you there.

Oleksiy Danilov, secretary of the National Defense and Security Council, did not need instructions from the president about where to go. He was one of the few officials in Zelensky’s circle who believed the warnings of an impending invasion. The prospect of this sometimes seemed to excite Danilov as much as it frightened him. He firmly believed that the Ukrainians would fight back fiercely, and he wanted to be on the front lines.

On the morning of the attack, he was already dressed when the first Russian missile hit an air base near his home on the outskirts of Kyiv, so close that his windows shook. The impact gave him an unexpected feeling of relief, he later recalled. His wife and son had already left the city in advance of the attack, and Danilov found it distressing to live alone with the expectation that an offensive could begin at any time. Now the wait was over and he knew what to do, what defense mechanisms to put in place.

As Danilov turned onto Bankova Street, he noted the time – 5:11 a.m. – and trudged up the stairs to Zelensky’s office. He was surprised that the president was wearing a crisp white shirt. The choice seemed inappropriate and somewhat out of character. Zelensky was known for coming to work in his lucky green and black sweater, which was more reminiscent of a Star Trek convention. But on that day of all days, he decided not to keep it casual. He was dressed like he was about to go on stage. The other surprise was Zelensky’s appearance. He was calm, his voice firm, his eyelids relaxed. The first statement about the war he made to Danilov was the same one he had made to his wife an hour earlier: “It has begun.” Then he asked a profane question that is difficult to translate from Russian. Roughly speaking, it means: “Do we want to kick their asses?”

For now, however, it was mainly the Russians who were kicking others’ asses. In the initial stages of the invasion, some seventy thousand soldiers and seven thousand armored vehicles advanced on Kyiv from the north, on both sides of the Dnieper River, which flows through the city. It appeared to be a blitzkrieg, similar to attacks the Kremlin had carried out over the years with devastating effect. In Operation Whirlwind in 1956, Soviet forces needed less than four days to occupy the Hungarian capital and overthrow the government, whose prime minister was subsequently arrested, tortured, found guilty of treason in a secret trial and executed on the gallows two years later . In 1968, Soviet troops overran Czechoslovakia and captured Prague in two days, and on the evening of December 27, 1979, Soviet special forces needed just a few hours to storm a heavily fortified palace in Kabul and liquidate the Afghan leader.

Days before the invasion began, Ukrainian intelligence had tracked down three groups of assassins who had been tasked with killing Zelensky.

Danilov, who was interested in military history, had such precedents in mind when he tried to imagine the Kremlin’s plan to conquer Ukraine. He did not believe that the Russians could take and hold the entire country. It was too large, its territory was almost twice as large as Germany, and the population’s willingness to resist would not allow a quick occupation. What worried Danilov was the Kabul scenario, a blitz attack on the presidential office to capture or kill the head of state. Days before the invasion began, Ukrainian intelligence had tracked down three groups of assassins who had been tasked with killing Zelensky. All came from the southern Russian region of Chechnya, home to some of Putin’s most ruthless and loyal commandos. “We had been watching them for a while,” Danilov told me later. “There was concrete information that they were going to liquidate our president.” The daily intelligence report that Danilov received on February 22, two days before the invasion, included detailed warnings about the plot. That evening, Danilov brought the top-secret document to Zelensky’s office to inform him of the danger. But the president dismissed the whole thing. He refused to believe that in the 21st century, three decades after the end of the Cold War, hitmen were trying to assassinate a sitting European head of state. Nor could he imagine that Putin would start a major war, a land invasion on a scale Europe had not seen in generations.

“At the time we thought they were just threats,” Zelensky later told the BBC. »We have spoken to the secret services, our own and those of our partners. Everyone saw the risks differently.” Some of his European allies, including the leaders of France and Germany, assured him that American predictions of an invasion were exaggerated. “They called me back and told me: ‘We spoke to Putin. “Putin will not invade.”

They were wrong. At exactly 5:00 a.m. Kyiv time, the Kremlin released a video on its website to announce the start of the invasion. The footage showed Vladimir Putin in a wood-paneled office, with red eyes and a dry mouth; he held onto the edge of his desk with both hands as if he needed support. The list of enemies and grievances he cited to justify the war went back decades, and he never mentioned Zelensky’s name in this speech. Putin also did not name Ukraine as the ultimate target. In the first twenty minutes of his declaration of war, he focused instead on the United States, the wars it had fought in Yugoslavia, Libya and Iraq, and the “imminent threat” it posed, as he said, to Russia. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States has accepted more and more European states into NATO, Putin explained, and has expanded this “war machine” ever closer to Russia’s borders. NATO military bases are now located in the parts of Europe that Russia considers its legitimate sphere of influence, and he will not allow Ukraine to follow this path and achieve its goal of joining the alliance. In the “historically Russian country,” he said, meaning Ukraine, the United States and its allies have created a hostile “anti-Russia.” Sooner or later they would use Ukraine to start a war against Russia itself, and it would be “irresponsible” if the Russian military did not strike first and neutralize the threat.

If Zelensky’s rise to power in 2019 was based on his fame as a comedian, Putin’s rise was based on his victory in a war against Chechnya, whose cities he bombed, killing tens of thousands of civilians.

Like many of Putin’s tirades against the West in recent years, this speech was dripping with falsehoods and paranoia. In reality, the United States and its European allies had long refused to provide Ukraine with a clear path to joining the alliance. NATO leaders had delayed Ukraine’s membership bids for a decade and a half, and their concern about angering Putin prevented them from providing Ukraine with the weapons it needed for self-defense. Some of these concerns were undoubtedly justified. If Zelensky’s rise to power in 2019 was based on his fame as a comedian, Putin’s rise two decades earlier was based on his victory in a war against Chechnya, a breakaway state in southern Russia whose cities he bombed in 1999 and 2000, killing tens of thousands of civilians . The brutal subjugation of the Chechen population and the assassination of their leaders largely set the tone for Putin’s reign and presaged his attempt to do the same in Ukraine. While Western leaders wrung their hands and pondered the risks of escalation, Putin decided to attack Kyiv, and his speech left the world in no doubt about his intentions. The leadership in Ukraine, he said, was a bunch of genocidal neo-Nazis, and he wanted to overthrow their government, “demilitarize and denazify” their country and install a loyal leader in Zelensky’s place.

In those first hours of the invasion, no one could tell whether Zelensky and his team would hold out. The military and intelligence community had spent months drafting scenarios for the invasion, but their forecasts never settled the question. Would the president panic? Would fear of his own death affect his leadership skills? “That’s the one factor that you can never calculate,” Danilov said to me later. “Until you find yourself in this situation, you can’t say how you will react.”

History tended to prove the pessimists right. Just six months before the invasion of Ukraine, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani – a much more experienced leader than Zelensky – left his capital as Taliban fighters approached. One of Zelensky’s predecessors, Viktor Yanukovych, fled Kyiv when protesters laid siege to his office during the 2014 revolution. At the beginning of the Second World War, the leaders of Albania, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Poland, the Netherlands, Norway and Yugoslavia, among others, fled the advance of the German Wehrmacht and spent the rest of the war in exile. Even Ivan the Terrible, the first Russian ruler to call himself Tsar, fled Moscow when the Ottomans and their regional allies attacked the city in 1571.

As soon as the bombing began, some government officials turned off their phones, packed their cars and headed for the western border.

Little or nothing in Zelensky’s biography suggested that he would behave differently. He had never served in the army or shown any particular interest in its duties. His professional instincts were based on a life as a stage actor, a master of improvisational comedy and a producer for film and television. His experience as a statesman was approximately two years and nine months, less than the time it takes to earn a bachelor’s degree in international affairs. For almost anyone in his position, the impulse to flee would have been as natural as the will to survive. A few Russian bombs, like those that fell on the Ukrainian military bases that morning, would have been enough to devastate much of the government district and also destroy the parliament and the cabinet of ministers, both of which are located in the immediate vicinity of the presidential office. This part of the city, known as “the triangle,” had never been easy to defend. The demonstrators who drove Yanukovych from office in 2014 managed to take over parts of it with little more than shields and sticks. Now the authorities had to reckon with Russian tanks rolling through the city. When Danilov began calling government officials, he was not surprised to learn that as soon as the bombing began, some had turned off their phones, packed up their cars and headed for the western border. “A lot of them panicked,” he said.

There were defections that particularly affected Ukraine’s main secret service, the SBU. “There were a lot of problems, especially in the upper and middle ranks,” another of Zelensky’s top security advisers told me. “A lot of people in the security structures said, ‘Let’s get out of here. Resistance is futile. The Russians will defeat us.'” Their exodus decimated the organization’s upper and middle ranks. Dozens of officers switched to the invaders’ side, handing over the keys to parts of southern Ukraine. However, the leadership in Kyiv remained largely steadfast.

Zelensky will hold an emergency meeting on February 24, 2022

Enlarge image

At around 6:00 a.m., the Security Council met in Zelensky’s office on the fourth floor of the presidential office. The President sat at the head of the conference table facing the door. A brief report from the military commanders gave a sense of the scale of the invasion. The main target appeared to be Kyiv, where rockets hit a military command post, an ammunition depot, a National Guard garrison and other targets. Of all possible scenarios for the invasion, Russia chose the most aggressive, and Zelensky was forced to impose martial law across the country. The Security Council quickly agreed. Nobody raised any objections. Under the circumstances this seemed a formality, but the consequences were enormous, as became clear in the months that followed. Martial law enshrined in the Ukrainian constitution grants the president broad powers to rule by decree, such as suspending elections and other democratic rights and freedoms of Ukrainians for the duration of the war. For example, curfews can be imposed. Every man of fighting age between eighteen and sixty years is subject to conscription and is not allowed to leave the country. The normal functions of Parliament are suspended and the assets of state-owned companies and all private property may be confiscated in the interests of national defense.

Panic set in, and Zelensky realized that they could overrun the capital much faster than the Russian tanks.

Soldiers and volunteers had begun setting up barricades around the government district and blocking some streets with dump trucks and buses. Long lines formed at banks and gas stations throughout the city, and the main train station was full of people trying to escape. All flights to and from Ukraine were canceled. Passengers and airline staff were asked to leave Kyiv’s main airport. Panic set in, and Zelensky realized that they could overrun the capital much faster than the Russian tanks. He had to reassure people that it was safe to stay home. He made his first attempt at around 6:30 a.m.

He sat at his desk, placed his phone in front of him and pressed record. The sixty-six-second message showed little of the confidence that Zelensky exuded in his later war videos. Reading too quickly from a series of prepared notes, he informed the nation that Putin’s forces had invaded, that explosions had been heard across the country and that Ukraine’s foreign allies were already preparing an international response. Then he spoke more slowly and a faint smile crossed his face. “What is required of you today is calm, from each and every one of you,” he said into the camera. »I will be in touch again soon. Don’t panic. We are strong. We are ready for anything.«

The prepared part of his speech was true, the rest was not. Zelensky suggested in his video that people could feel safe at home, but he knew better. Some of his employees had already sent their families out of town and said goodbye to them as if it were the last time.

After martial law was declared, most members of the Security Council, including the heads of the military and intelligence services, left the presidential office and went to their respective headquarters to take command. They had a clear mission to observe the battlefield, collect information and direct the troops. The role of the president was less clearly defined. Although he was commander in chief of the armed forces, he had neither the experience nor the intention to lead them. Rather, he trusted his generals and focused instead on diplomacy, on the need to mobilize world leaders. The first number he dialed in his office that morning was that of British Prime Minister Boris Johnson. At that point – around 4:40 a.m. – it was still dark in London, but Johnson answered and greeted Zelensky warmly. The two had gotten to know each other better in the months before the war; Johnson tried harder than most of his colleagues to reassure Ukrainians and assure them of support. In the weeks before the invasion, his government had also sent one of the largest shipments of weapons, including anti-tank missiles. »We will fight, Boris! We won’t give up,” Zelensky shouted into the telephone receiver. A few steps away was Danilov, who found the scene so moving that he recorded it on his cell phone.

As dawn broke over Western Europe, other foreign leaders from Washington, Paris, Berlin, Ankara, Vienna, Stockholm, Warsaw, Brussels and elsewhere contacted Zelensky. Her calls lit up the secure phone on his desk every ten or twenty minutes. None of them sounded as encouraging as Johnson, and some issued veiled ultimatums to remind Zelensky of the danger he faced. “There were threats against the president that first day,” said foreign policy adviser Sibiga, who prepared the talking points for those calls and leaned over the president’s desk to listen in. “The core message was: Accept Russia’s demands or you and your family are dead.” Several of the foreign heads of state offered to act as a mediator for Ukraine to negotiate the terms of surrender. »There were offers along these lines: accept the conditions. Think about who you’re dealing with!”

With an estimated nine hundred thousand soldiers on active duty, Russia’s military was at least four times as strong as Ukraine’s. The Russians had five times as many armored fighting vehicles and ten times as many aircraft. At around $4.5 billion, Ukraine’s defense budget was about a tenth of what Russia spent annually on its military.

Zelensky’s allies knew the balance of power – and what it meant. That’s why at the beginning of almost every phone call they asked him whether he wanted to leave Kyiv for his own safety and how they could help him. The presidential guard had a list of safe places where he could go. Bunkers were available on the outskirts of the capital. Further west, near the border with Poland, various government institutions offered the president the opportunity to govern without the immediate threat of assassination or encirclement by Russian troops. Several European heads of state agreed to help him, his family and his colleagues escape. One of the safest options was to direct Ukraine’s defense from a facility in eastern Poland that was under the NATO alliance’s nuclear umbrella. US officials, including President Joe Biden, were willing to help Ukraine set up a provisional government in exile.

Zelensky appreciated such offers, but also found them a little insulting, as if his allies had already written him off. “I was tired of it,” he later said of the offers of escape that, as he said, “came from all sides.” He tried to steer every conversation toward what Ukraine needed to defend itself—namely large arms shipments and the closure of its airspace—and became angry when he subsequently received further offers to help him escape.

“Sorry,” he said, “but that’s just not appropriate.” The frustration was evident that morning in a conversation with French President Emmanuel Macron, who put the phone on speaker so his advisers could listen to Zelensky’s account of the start of the invasion. “This is total war,” said Macron. “Yes,” came the answer. “Total war.” Zelensky took a deep breath. If the Russians intended to take Kyiv within days, he could not trust that the West would supply weapons quickly enough to improve his chances of survival. He also realized that the United States and Europe would not risk nuclear war with Russia by sending their own troops to rescue Ukraine. Western leaders, including President Joe Biden, had made this clear to the Ukrainians. Zelensky’s only hope, however naive or delusional, was that the West could persuade the Kremlin to call off the attack and withdraw its troops. “It is very important, Emmanuel, that you talk to Putin,” he said to Macron. »We are sure that the European heads of state and government and President Biden can find a connection with him. If they call him and tell him to stop, he will stop. He will listen.”

At his home in Koncha-Saspa, the president’s family waited for his call. His children were already awake when Olena went to wake them up. She was unsure how to break the news of the invasion to a nine-year-old and a seventeen-year-old, and Zelensky hadn’t given her any advice. “He didn’t say that I should be honest or dishonest with the children,” she said of her last conversation at home. “He just said that I should explain everything to them.” None of the children asked many questions.

Kyrylo, a playful, sensitive boy who was easily distracted, obeyed his mother with quiet determination and stuffed a few of his things into a small backpack: some pencils, a puzzle book, pieces of a half-finished Lego set. Oleksandra, who the family calls Sascha, kept in touch with her friends on social media, trying to get a better picture of what was happening outside. The extent of the danger was difficult to grasp from the news and television broadcasts. The headlines focused on the immediate facts—the impact of a missile, the sighting of a tank—leaving people to guess at the bigger questions, such as their country’s prospects of holding out.

Through the windows of their home, Zelensky’s family could hear the roar of anti-aircraft batteries trying to shoot down Russian missiles, planes and helicopters. Once, as the first lady stood at the window, a fighter jet roared through the sky, flying so low that she felt the noise in her chest. Her bodyguard advised her to take the children to the basement. There was a risk that the Russians would bomb them from the air. Her smaller dog, a miniature schnauzer, was terrified of fireworks and thunder and was in shock from the noise of the explosions. Olena picked him up in her arms and carried him down the stairs. That morning they repeated these steps several times: They waited in the basement until security said it was safe to go upstairs, then put a tea kettle on, which came to boil just as the next air raid alarm sounded them forced back into the cellar. Nevertheless, Olena did not want to flee Koncha-Saspa. When the president finally called, she told him that she felt safer at home than in an unfamiliar place and that she didn’t want to leave her pets behind. “We tried to argue, but he told us it was pointless.” The address of their house had long since been published in the press, and they had to assume that the Russians had circled Koncha-Saspa on their maps.

Without knowing where they were going or how long they would be gone, Olena picked up the family documents and packed a rolling suitcase for herself and the children. The pets were left in the care of the maid and security guards, some of whom remained on the property. As they drove off, there was panic in the city and suburbs. Traffic had shifted from the highways to the country roads. Huge queues had formed at gas stations and the first barricades were erected near the city center in anticipation of the Russian tanks. On Bankova Street, the guards led them up to the government floor, where things were tense but not chaotic. No one screamed or showed much emotion. The loudest noise came from the metal detector in the fourth floor hallway, which beeped every time a soldier with an assault rifle rushed through. Otherwise the tone was muted. The employees huddled near two ferns by the window or stared intently at the screens of their laptops or phones, writing speeches, sending messages, following the news. “It’s hard to be prepared for this,” said Andriy Yermak, the president’s chief of staff, who had been at his side since early morning. “We had only seen something like this in films or read about it in books.”

Like many of the president’s advisers, Yermak came from the entertainment industry. His face was round and unshaven. On his wrists he wore folk bracelets made of leather and wooden beads. As a film producer, he was responsible for several gangster films that were very bloody and peppered with macho dialogues. Before his friend became president, Yermak worked as a lawyer for Zelensky’s production company. Now he was tasked with directing a war and fielding calls from generals at the front and from the White House. At some point that morning, Jermak looked at his ringing cell phone and recognized a familiar name on the screen. It was Dmitri Kozak, a senior Kremlin official whom he knew well from previous peace talks. They had held a secret dialogue for weeks and tried in vain to find an arrangement that could have persuaded Putin to call off the attack. The talks failed. This time Cossack called with a different message. Ukraine should surrender on Russia’s terms. Yermak let him finish, then told him to go to hell and hung up the phone.

If he had been afraid at that moment, it wasn’t for his own safety, he later remembered. Fifty-year-old bachelor Yermak had no family to evacuate from Kyiv and had therefore decided to stay by Zelensky’s side no matter what. Many of his colleagues couldn’t make this decision so easily.

Some arrived on Bankova Street that morning with their families and luggage in their cars, expecting an organized evacuation of the presidential staff. Zelensky did not stand in their way. As long as these employees asked for permission to take their loved ones out of town, they were allowed to leave. “We are all human,” he said. “And some quick decisions had to be made.”

The president, for his part, decided that his family had to flee. The risk of bombing was far too high, and he placed stricter demands on their safety than on his own. The farewell that day was unsentimental. The presidential family didn’t even go into a private room to talk. They hugged in the hallway and exchanged a few hurried words as Zelensky hurried from one meeting to the next. His wife doesn’t remember him giving her any assurances. After almost two decades of marriage, the brevity of the farewell did not surprise her. She knew from painful experience that her husband put his work above all else. As they stood there in the hallway, Zelensky didn’t promise her that everything would be okay.

“He knew that would have just made me panic,” Olena told me later. The danger was still abstract to both of them, and the First Lady’s reaction was to feign calm. “It couldn’t be a desperate farewell,” she said. “The children don’t need something like that.” Her performance for the children made the situation seem less serious. “It was like I was going on vacation,” she said, “a completely normal, calm conversation before leaving.”

In reality, Olena and the children were running for their lives. There was a train at Kyiv’s main train station that was supposed to take them out of the city, although their destination was a secret even among the president’s closest confidants. On the instructions of the presidential guard, the state railway had a locomotive ready to depart in case Zelensky decided to leave the capital. Every now and then a group of security guards walked through the carriages, checking for threats in anticipation of his arrival. But Zelensky didn’t come. His family’s train left without him, rattling out of the station with his wife, two children, their team of bodyguards, and their trolley suitcase.

Translated from Spiegel article, for my friends