by ASYA TSYSAR

The word “circumstances”, which my silent Russian family uses instead of the word “war”, somehow harmoniously complemented the moment when we felt like a family for the first time in many years.

My grandmother on my mother’s side was called Nina. I didn’t know her. She died a few years before I was born. What did she like, how did she spend her free time, was she funny, was she happy? In our family, we don’t share stories, we don’t gather around a big table, we don’t remember the past. This story could be different, but it will be – fragmented and full of Google searches.

I could call the family, ask what they remember. But our last conversation was short: on February 24, one of them sent an icon of the Virgin Mary to the family chat with the inscription: “The best thing we can do in difficult times is to continue living a normal life.” For the past year and a half, no one from my silent Russian family has asked how I am.

When my grandmother was little, she was told that somewhere there is a place where apricots fall just outside. At least that’s how they always answered my question about how my grandmother ended up in Ukraine. “She dreamed of living where apricots fall on the street,” they told me.

Grandma Nina was born in Shegultan. This is written in the family album: “Urals, Sverdlovsk Region, Shegultan settlement.” The Internet does not know such a settlement, claims that Shegultan is a river 97 kilometers long. This is a Mansi name, which has greatly changed its phonetic appearance as a result of Russian assimilation.

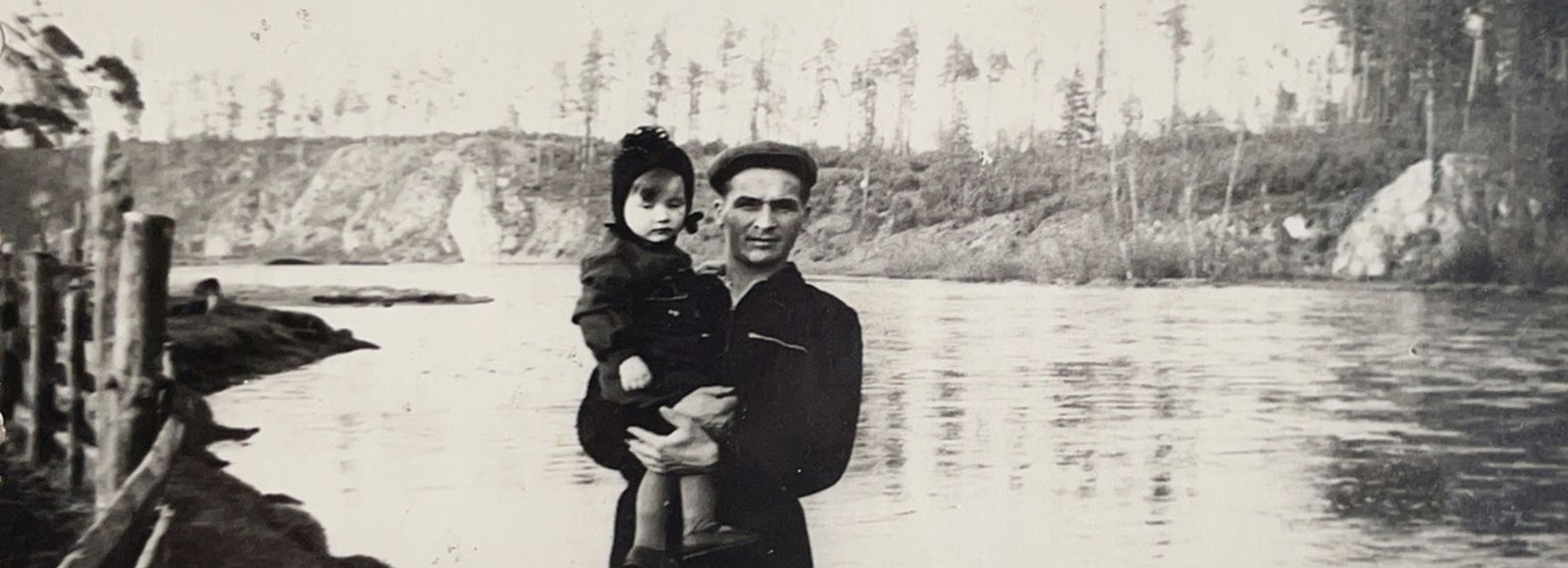

Photo from family archive

The Mansi are a nomadic people, the indigenous population of the Urals. Mansi belongs to the Finno-Ugric language group. This means that the Mansi share their origin with the Finns, Estonians, Hungarians and those who were later called “Russia” and after that did not have a chance to have their own state – Khanty, Vod, Karel, Nenets, Izhora. There are a little more than 12,000 left in Munsi, the majority still lead a nomadic lifestyle. 8% of them speak the Mansi language. This is approximately 960 people. Mansi, like Khanty or Nenets, is written in Cyrillic because the Soviets wanted it that way. (Yazyky i pismennost narodov Severa, G. N. Prokofiev, 1937) Before the Soviets, the Mansi did not have a written language. This means that the knowledge of how to deal with a herd of deer, collect plagues or process leather, as well as what day it is today, who they are and where they came from – all this Mansi had to tell each other. Maybe this is another proof that my silent family was not local in those parts.

For the past year and a half, no one from my silent Russian family has asked how I am

From Shegultan to the city of Zlatoust on the Russian-Kazakh border is 765 km. It is a seven-day journey on foot, if you walk without a break. My grandmother’s family came to Shegultan from the Zlatoust neighborhood because they were “dismissed”. Like the statement about apricots, this phrase never had an explanation in my family. Zlatoust (and the entire Chelyabinsk region) is another part of the Urals taken by Moscow. This is the land of Tatars, Chuvashians, Mordovians and Bashkirs.

From Shegultan to the village of Kamenka in the Sverdlovsk region, where my grandfather was born, is 488 km or 6 hours and 25 minutes by car. Grandfather’s name was Vitaly Spiridonovych, but everyone called him Tolya. He left me several carved pieces of wood and a notebook with poems. From that notebook, I learned that dyslexia is genetically transmitted. As an inheritance from my grandfather, I confuse “b” and “d” in writing, and in a strange way, these two letters made us closer than all the summers we shared in the country.

I don’t know if my grandmother was happy when she was in the place where the apricots fell, but I know from my grandfather’s notebook that he missed home and the place where he grew up. Almost all his poems are about this. And also about work in the North, about nights in tents, mines and rafting on frozen rivers. My grandfather was a prospector in the Ural mines, then a truck driver. When he was alive, I asked him almost nothing. At first it was too small, then it was too patriotic.

As an inheritance from my grandfather, I confuse “b” and “d” in writing and in a strange way these two letters made us closer

My grandfather died when I was finishing the ninth grade, the peak of my youthful maximalism. Then, in a Russian-speaking city and a Russian family, I switched to Ukrainian. My mother said that I would outgrow it, my grandfather was angry and pretended that he did not understand when I addressed him in Ukrainian. He was already sick, he lived with us during the break between operations. I was eating soup in the kitchen while I was retelling a school lesson about the Ukrainian national resistance and the Red Army. Somewhere in the tone of my voice there was a reproach that there was no heroic history of national consciousness and struggle in my family. I needed such a story to tell it to my classmates, but also to prove to myself: I am not here by chance, generations of my family also contributed to the history of Ukraine. Suddenly, without taking his eyes off the soup, grandfather said: “When there was a war, we mined gold in the Urals for the front. There were no machines, we dug by hand. The change was carried out underground, then the pieces of rock were washed in a sieve until no golden sand remained. And when there was hunger, my mother left me at the station. I was the youngest. She knew that she would not feed five children and someone would have to die. She thought that someone would take me. My mother left me on the platform near the bench, told me to wait and that she would come back, but she didn’t. I stood there and cried. Day and night. She came the next morning. She cried. Took me away. I never remembered that day again.”

My grandfather said that it was a famine after the war, and I believed him for a long time. But he was lying. Grandfather corrected his own memories. In 1945, he was 18, he had been working at the mine for four years and could hardly cry all night at the station bench. He spoke about the famine of the 1930s. In 1933, he was just six years old. Sometime around then, hunger forced his family to leave Kamenka. Somewhere along the way, his mother left him at the train station. Due to hunger, they ended up in Severouralsk. No one told me about this, I guessed it myself. In those war poems, where the grandfather is 14, he mentions mountains and trenches. Google says that those mountains are located around the Russian city of Severouralsk, which was not yet a city at the time, just another point of “exploration” on the large Soviet map.

Grandfather said it was the famine after the war, but he corrected his own memories

There, in Severouralsk, grandmother and grandfather met. They got married there in 1956. This is what is written in their marriage certificate. My aunt Natasha was born there. I look at an old family portrait against the background of their home. In the photo, they seem to be glued to the landscape, which I learned about only from TV – snow-capped mountains, cliffs, mountain rivers, trees that are older than the people themselves and their language. “In the Urals”. Another phrase I have heard since childhood. No one ever got me on their knees to tell me where it was. Nobody, it seems, even remembered. But Ural was always present somewhere in grandfather’s yawns and in mother’s sadness in her eyes. Ural, whatever it is.

They moved to Ukraine in the summer of 1962. Probably, the grandmother told her husband that she dreams of living where apricots fall on the street. They moved to Marganets, Dnipropetrovsk region. “And what exactly is Manganese?” – I ask my mother and aunt. “We never talked about it.”

Manganets is, of course, a Soviet city, a Soviet name. The world’s largest manganese deposits are located around the city. In 1962, the city was 24 years old, six years younger than my grandmother. Before the Soviets turned it into a “pearl of industrial culture”, this place was the center of the Scythian state, and then the first Zaporizhzhya Sich.

Between Severouralsk and Marganets – 2856 km or 38 hours by car without stops. I wonder what my grandparents thought about when they went to Ukraine? Was it imagined as I imagine a journey to distant Damascus? Were you worried that this place will be foreign and unfamiliar? That it will be necessary to adhere to local customs, learn to live by their routine and rhythm. They had never been here before moving. They couldn’t help but think about it as they changed four time zones.

“You have to understand, they weren’t going to another country, it was all one country,” my mother tells me, and I believe her. Grandma and Grandpa went “to Ukraine”, not “to Ukraine”, and it seems those damn two letters actually have meaning. What did it mean for someone who lived in the Urals to go to Ukraine? How was it different from going to the Caucasus? My grandparents were Russians, and this means that Russia defined a living space for them – “habitat area”. Maybe Ukraine is just the best they had to choose from? On Yamal, on Chukotka, on Sakhalin, on Novgorod. To Berlin. This is not a place, but a direction. Grandfather and grandmother went “to Ukraine”, as others go to the right or left, north or east.

In Marhanka, they lived in the corridor of someone’s private house. This is what happens when the state prohibits official leasing and leaves entire industries in the hands of the shadow market. Without a residence permit, Aunt Natasha could not go to the second grade. It was impossible to find a job in Marganka without a referral. In the corridor, even if you are a Soviet person, you will not live long. But that summer, as it always happens in the south of Ukraine, apricots fell on the asphalt.

Grandfather and grandmother went “to Ukraine”, as others go to the right or left, north or east

They moved to Dniprorudne, another young city that did not exist before the Soviets. It received the status of a city only in 1970, and was founded in 1961 as the village of Druzhba. A year before, geologists confirmed the presence of iron ore deposits with an extremely high iron content on the banks of the Dnieper, a unique deposit for Europe. In 1964, when my grandparents came there, the village of Druzhba was transformed into the village of Dniprorudne. I think there is no need to explain the etymology of the name.

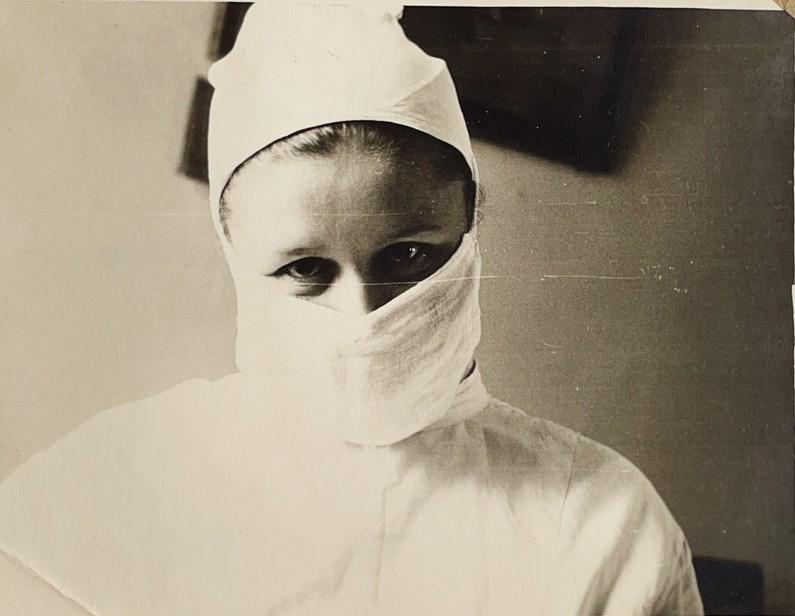

Dniprorudne lies on the opposite bank of the Dnieper from Marhanets. There was a lot of work there and no one asked about “direction”. It was a new city, everyone was a visitor there. In Soviet families, and my silent family definitely belongs to them, they talk about their loved ones according to the principle of the “autobiography” document, which is attached to the personal file folder on an A4 sheet: they moved to the city of Dniprorudne. They lived in a dormitory, later they got an apartment. Two rooms at the address st. Shakhtarska 5. Daughter Natalya went to school. Nina got a job as a nurse in a city hospital. Vitaly Spiridonovych worked as a driver at an iron ore enterprise. On December 1, 1966, the couple had a second daughter, Marina. All details are a secret. “They lived – and they lived,” my aunt said to my next question.

No one ever said it, but somehow I know they were happy there. Maybe by the way my mother’s eyes sparkle when she remembers how my grandmother gathered her friends to make dumplings. Maybe by the way they squint in old photos from the beach of the Kakhovsky Sea. And maybe because every time I walked through their sun-drenched yard, I could see my mother’s childish laughter as an adult. There is such a strange type of vitamin D-saturated southern Ukrainian happiness. It comes imperceptibly, clings like dust to sweat-damp skin. This happiness is quiet, like shoes taken off at the end of a hard day, or a glass of water drunk in the heat. Grandmother lived in the south of Ukraine for 12 years, grandfather — 37, aunt — 22, mother — more than 40.

“Let’s come,” grandmother wrote in every letter when grandfather returned to the Urals to earn money in the early 1970s. New promising deposits. This time, gas deposits. Grandfather always replied to those letters: “No need.” They had not seen him for several years, they did not even know where he was. A closed settlement, a piece of the map erased in the interests of state security. An envelope with a letter and money came to my grandmother regularly once a month. When instead of letters, only money began to arrive, my grandmother packed a suitcase, took my five-year-old mother and boarded a train going to the Urals.

“We traveled for a very long time, probably more than a week. In the end, they reached Novy Urengoy airport, because it was the final address of my father’s letters. Mom talked to someone for a long time, asked to call dad or to inform him that we are here and to pick us up. She was told that it was forbidden, that the settlement was secret and that women with children had no place there. Mom said she wasn’t going anywhere, and we lived in the airport for another week, until dad arrived in a helicopter and, with pipes and batteries, took us to Nadym.

As a child, I remembered only the word “helicopter” from this story, and therefore always dreamed of flying on it. But in my imagination we never fly over the city, only always over an endless snowy void, without people or houses. When I was growing up, my mother would end any question I asked about her childhood, school, grandmother, or even when I didn’t ask anything at all, with this story. Each time, an invisible “something” squeezed her throat and for a second she became a frightened child stuck in an empty airport.

As an adult, I enter “Noviy Urengoi Airport” in the search box and come across a photo of a wooden house in the middle of a snow field. I sent the photo to my mother with the question “is this the airport?!”

In Nadym, in Novy Urengoy, in Salekhard, and in Tyumen, Tatars and Ukrainians are the second largest population after Russians, followed by Kazakhs, Belarusians, Moldovans, Bashkirs, Kumyks, and Chechens. The Khanty and Nenets – the indigenous population – are included in the “other” category, because there are not enough of them left for the statistics to give them even a fraction of a percent. This is written in the book “Heart of Yamal”, published for the thirtieth anniversary of the Nadym settlement. And it also says that in the 1930s, the indigenous population experienced a “civilizational leap” here. The Soviets brought collectivization to Yamal, but only disorganized the tribes that led a primitive way of life. Tribal leaders were called “kulaks” and sent to concentration camps; the Russians redistributed their ancestral territories to collective farms, and some of the locals were forced to engage in experimental agriculture – Soviet scientists tested the frost resistance of beetroot and potato species at the Arctic Circle. In 1936, a pioneer camp was opened for Nenets children. In 1937, traders at the exchange markets were obliged to have mirrors and hand washers in their assortment of goods, and for the first time among women, a competition for the best housing – chum – was organized.

The Khanty and Nenets, the indigenous population, are classified as “other”, because there are not enough of them left for the statistics to give them even a fraction of a percent

Five years later, 70% of the men of the indigenous population were drafted into the Red Army. There are no exact statistics on how many of them returned home. In the second half of the 1960s, Moscow discovered Yamal for itself for the second time – promising gas and oil deposits reoriented the Soviet economy and became one of its main priorities. For the first time, the almost uninhabited lands of the Arctic region are populated en masse with workers from the Union republics. At the same time, the second city in the history of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District – Nadym – appears on the map.

Mom calls me 6 hours after my message with a photo of the airport: “We talked with Natasha, tried to remember how everything was.” This isn’t the first time I’ve asked a family history question, but it’s the first time it’s led to my mother having an hour-long conversation with her sister, including one where they tried to piece together the fragments of memories into their own story. I learn that my grandfather did not work in Nadyma, but somewhere in the tundra. While they were waiting at the airport, he tried to transfer to another job so as not to take his wife and daughter to the workers’ tents. Their crew cleared the forest for a gas well and built pontoons, because the forest was virgin and the rivers had never been bridged before. I remember that my grandfather has a poem about this and I read it to my mother. One and then another. About how he really missed them in those woods. Mom laughs childishly.

This story leads to another. Mom remembers how her grandmother’s hair peeked out from under her fur hat. This is how I first learned that Nina’s grandmother dyed her hair ruby. You can’t make it out in black and white photos. When the liveliness of the conversation gives way to a pause, mom says: “Aunt Natasha asked you to tell me – no matter what happens, we’re still family, and that’s more important than all the circumstances.” I don’t answer. The word “circumstances”, which my silent Russian family uses instead of the word “war”, somehow harmoniously complemented the moment when we felt like a family for the first time in many years.

I learned for the first time that grandmother Nina dyed her hair in the color “ruby”, you can’t tell from the black and white photos

Balók, with an emphasis on the last syllable, is my mother’s happiest childhood memory. A balók is a freight car, or more often, a freight car tank that stands on self-made skis instead of wheels. In such a cistern, a door was cut, a corridor was completed, it was insulated from the inside with a layer of cotton wool and plywood, and then with putty to glue the wallpaper. Grandparents’ cabin had a kitchen and two tiny rooms. This settlement was supposed to serve the construction of the city. The city was built to serve the gas field. In that long conversation, Aunt Natasha told my mother that Nadym, now one of the largest Russian cities in the Tyumen region, will no longer be developed, because the gas field has been exhausted. But, they say, there is nothing to worry about: another deposit has already been found a few hundred kilometers away, and workers are already building a new city there!

When my grandfather brought my mother and grandmother there, there was no sewage, gas or water supply in the settlement. Water was brought by water carriers and poured into barrels standing near each beam. The water in them froze, and when you wanted tea, you had to break off a piece of block and put it in a bowl to drown on the stove. The family lived in such a building for nine years. In the spring and autumn, the children had fun jumping over the marshy mounds. In winter, they warmed themselves with dumplings filled with raw smoked sausage, because meat was not brought across the Arctic Circle. In children’s photos, mom always has puffy cheeks. “It’s diathesis from the vinegar,” she says. “There were no fresh vegetables or fruits. Conservation itself.” Sometimes, on the way from the beam to school, my mother saw runaways, convicts, as they were called in Nadyma. Sometimes they sneaked into settlements and stole food that residents hung outside the window due to the lack of a refrigerator. Mom says that the convicts were scary, and that the men drove them away with guns. And my mother says that every year she looked forward to two things: when they would build ice slides on New Year’s and when they would go to the sea in the Crimea in the summer.

“Thank you for the tights,” “Mayonnaise didn’t break,” “We’re giving Tane calico sliders,” my mother, a third-grader from Nady, wrote to her sister in the Ukrainian city of Dniprorudne. I mentally reproach her: where does such practicality come from in the third grade? I complain that maybe the letters in which my mother described her everyday life, lessons or first loves were simply lost somewhere and I will never learn about my mother’s first love and the advice her older sister gave her. But in my heart I know: such letters never existed, even if I reread everything my mother wrote then. I know because I am her daughter. It is not customary for us to talk about such things. “What do you want to convey?” – my mother still asks me every other sentence after “Hello”.

While my mother was a schoolgirl, a piece of virgin tundra turned into a hundred five-story buildings, three schools, a department store, a hospital and a square where a holiday was held every year – the Deer Herder’s Day. In 12 years, the population of Nadym grew from a few hundred to more than 25 thousand. In my mother’s graduation album, classmates wrote wishes and addresses to continue friendship in correspondence: Ukrainian Kherson, Kirovohrad, Berdychiv. In that place (it is absurd to call a settlement for the maintenance of mineral extraction a city) everyone was temporarily. Everyone came to that place from somewhere and everyone knew where they would return to later. In the year when my mother finished school, and my grandfather and grandmother retired, they returned to Dniprorudne, Ukraine, where my aunt had been waiting for them all these years, already with her own family. My mother entered the institute, and my grandmother died of cancer. The disease killed her in three years. The doctor said that one of the reasons was a sudden change in climate — the difference in average annual temperature between Nadym and Dniprorudny is about 40 degrees. We also never talked about my grandmother’s death, and my grandfather never really experienced it. He did not remarry, he did not look for another woman at all. He never changed the furniture in their apartment, only decorated what they already had with carvings. Until the end of his life, that is, 20 years after her death, he went to her cemetery every week.

Everyone came to that place from somewhere and everyone knew where they would return to later

Grandfather was an atheist and an almost cinematically Soviet person. He didn’t believe in God or an afterlife, but he still went to see his grandmother every week. There, in the cemetery, he never spoke to her, never greeted her, never cried. Digging the earth, planting flowers, and writing words on her tombstone in gold paint were his silent prayers. But he never told us about this either. I only know this because he took me with him when I visited him during the summer holidays.

After graduating from the institute, Aunt Natasha’s husband received a job referral to the Luhansk region. The aunt locked herself in the chief’s office and screamed until she burst into sobs. She begged not to send them to Luhansk. “Ukraine means poverty!” she said. Through her grandfather’s friends, she sent her husband to work in Nadym and, like a grandmother, took her daughter and went to the Urals. History has made its circle. They went to earn money and, like everyone else, they knew that they would return. When in the 1980s the company rented out cottages, they took a plot near Dniprorudny. When Gazprom distributed apartments in the 2000s, they took a three-room apartment in Dnipro, because it was the closest to the place they wanted to return to. When in the 2010s the existence of a state border, or the border of the “area of promise” became more obvious, aunt and uncle planned to move to Russian Belgorod, they just had to wait for retirement. After all, in those artificial Ural cities, everyone lives only until retirement, and then, having earned or worked for a living, they go to the sun and fresh fruit.

“Ukraine means poverty” – they say in my Russian family. Although there is no logic in living in a snow-covered cistern in the middle of the forest and considering this life “richer” than the one they left in Ukraine. There was no logic in sending me a Soviet desk by post from Nadym to Zaporizhzhia in the 2000s, because the same one could be found in the “Furniture” section of local newspaper ads. Every summer, my aunt and her family came from Russia to us in Ukraine, and every time they brought some things that didn’t make sense – a radio that looked like a vacuum cleaner; duster in the shape of a rocket; travel bag, curtains. They gave them to us because we were “poor”, and in their opinion, we were “poor” because we “lived in (on) Ukraine”. And every summer we went to the sea together in the Crimea.

When I was little, my mother said: “We should go to the Urals.” When I grew up, my mother used to say: “Just imagine, if we did go, you would have finished school in Nadym. You would never know that you are Ukrainian. If you were Russian, everything would be different.” My mother never returned to the Urals, and I never became a Russian. Without knowing it, mom violated the main rule of the “living area” – the functionality of the space. They earn money in the Urals, retire “in Ukraine”, rest at the sea, cook in the kitchen, sleep in the bedroom. Mom was stuck in the place everyone was supposed to return to. But no one came. In 2014, it was finally resolved. No one said it out loud, it’s just that my aunt Natasha stopped mentioning the move. The Revolution of Dignity destroyed the biggest dream of my mother’s life: “So that we all live together.”

They earn money in the Urals, retire “in Ukraine”, rest at the sea, cook in the kitchen, sleep in the bedroom

The story about apricots does not give me peace. Grandma’s family brought it from the Russian Zlatoust, so maybe the apricots fell somewhere on the Russian-Kazakh border? After several consultations, I got the answer: apricots grow in the south, but there are none in the northern regions of Kazakhstan, the climate is not the same. In this silent family, I am not the first to try to unearth my roots. I am a friend. My great-uncle, an amateur historian from the Urals, wrote a book about the history of his family. He begins it with the campaign of Yermak – the leader of the Volga Cossacks, who won the Siberian Khanate for Moscow. Uncle writes that this event is the beginning of the “Russian” history of Siberia. Immediately after the conquest, the policy of Christianization and settlement of lands by those whom Moscow considered “Russian people” was carried out. This fate befell not only the Urals and Siberia, but also Kazakhstan, the Caucasus and most of the territories that were once called Russia. It was because of these conquests that my family, together with packages and chests, brought to Chrysostom the story of the house they had left, the house where the apricots fell. Maybe that’s why I’m Ukrainian. Maybe that’s why the road to my grandfather and grandmother’s grave in Dniprorudny is covered with wild apricots. Perhaps that is why Dniprorudne has been occupied by Russia for a year and a half.

The essay is part of the Taking the Train East project and was written thanks to the Open Place residency and the Locus School’s Essays for Public Debate program.

Published with the financial support of the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation.

The Ukrainian department also works thanks to the funding of the Juliusz Myeroshevsky Dialogue Center.

Translated by John Gather – Original in Ukrainian – Availabe in Polish