“And I made an important conclusion for myself: we must not forget about this time, we must talk about it, talk about the people who suffered under the regime. If we do this, perhaps this will not happen again in our country.”

Evgenia Chubukova

Personal experience: Evgenia Chubukova

07.31.2020

I was born in post-Soviet times, and there was no longer any point in hiding from me some facts from the life of my relatives. My family told me stories about wealthy relatives in the Kaluga region, about Moscow merchant relatives who traded either threads or horses before the revolution. They also talked about my great-grandfather. Great-grandfather repressed in 1937.

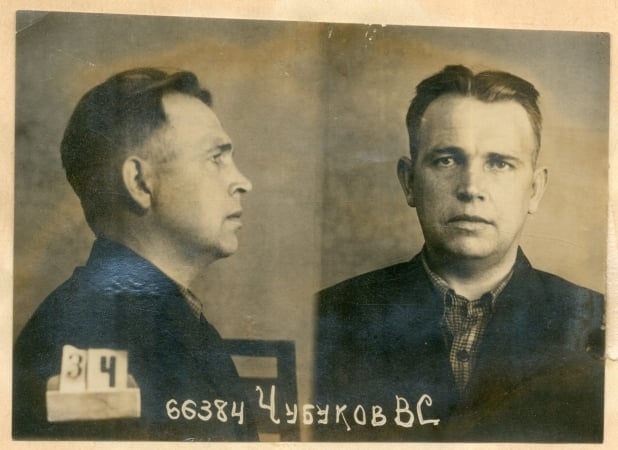

Chubukov Vasily Stepanovich is the father of my maternal grandfather. Grandfather never spoke in detail about his father, and I didn’t see Vasily Stepanovich himself or his great-grandmother. For this reason, I learned their life story from the younger generation.

Little was known from the words of relatives. Vasily Stepanovich worked as chief accountant at a plant in Moscow. His date and place of birth were not known, nor was the date of his death. He had two sisters, but contact with them was lost long before I was born. In 1937, when my grandfather was about a year old, my great-grandfather was arrested and sent to a camp. My great-grandmother, as the wife of an “enemy of the people,” was exiled with her little son to Kazakhstan, where she spent several years. Vasily Stepanovich himself returned to Moscow only in the early 1950s.

None of the family knew exactly why Vasily Stepanovich was arrested. According to one version, the case was somehow connected with a scarf on which the Russian emperor was depicted, according to another version, with an anecdote about the murder of Kirov. They said about my great-grandfather that he was a straightforward person and that this was also one of the reasons for his arrest. I will have the opportunity to verify this.

I have always been interested in my ancestry and in 2017 I decided to find an archival investigative file on my great-grandfather, Vasily Stepanovich. First, I studied the open databases of the repressed, where I found my great-grandfather, but there was little data there. Next, I used the help of the project website “Everyone’s Personal Business”. On the main page, in the “Get information about the repressed” section, I used a diagram that indicated the necessary steps for the search, sample requests and addresses of authorities where the file could be stored. I didn’t wait long, downloaded the sample, filled it out and sent it to the relevant departments.

I made several requests: to the Central Archive of the FSB of Russia (Bolshaya Lubyanka Street, building 2), to the FSB Directorate for the city of Moscow and the Moscow region. After 20 days I was told that the file was kept in the State Archive of the Russian Federation.

I didn’t wait for notification from the archives, and went there myself with a thick folder of documents confirming the relationship. At the archives, I was immediately taken to the appropriate specialist to submit a request, and after about 2 weeks I was invited to the reading room.

I was immediately warned that I had no right to take photographs and could submit a request for copies of only 20% of the file. It turned out to be medium in volume – about 50 sheets. To be honest, you experience a strange feeling when looking at a criminal case with your last name on it.

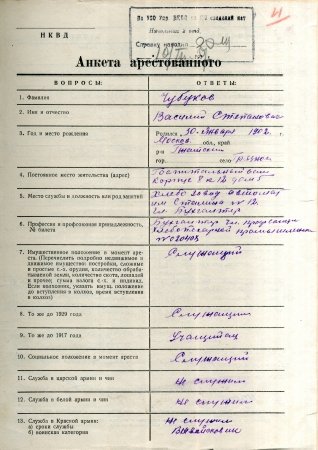

The arrestee’s questionnaire is one of the most important and informative documents in a criminal case. From the questionnaire I learned that Vasily Stepanovich was born in 1902 in the Smolensk region and by 1937 he worked as chief accountant at bakery No. 12 named after. Stalin in Moscow. Vasily Stepanovich’s family consisted of two sisters, a wife and a ten-month-old son.

The task of the investigation is to restore the chronology of events and crimes and find the culprit. Hands, however, have difficulty typing this in relation to the 1937 case. And now, 80 years later, I plunged into the records of interrogations, confrontations and indictments to find out what happened.

On February 21, 1937, my great-grandfather came to work as usual. The accounting department had a common room for employees and, being the chief accountant, Vasily Stepanovich had a separate workplace slightly away from the rest of the employees. Approaching his desk, he saw some kind of rag on the floor, which turned out to be a handkerchief. Vasily Stepanovich loudly asked his colleagues who dropped the handkerchief, but received no answer. Having started to do work, he asked his subordinate, who was closest to the scarf, to hang it on the crossbar under the table, that is, in a visible place. Then, during interrogations, he said that he did not take other people’s things and ordered to hang the scarf so that the owner would still find the loss. And this was the first unintentional mistake.

After some time, when my great-grandfather was not at work, an employee of the bakery, Levashov, came into the accounting department. According to this man’s testimony, he immediately saw the hanging scarf and decided to see what it was. Having examined the scarf, he took it off the crossbar and took it away in an unknown direction.

The second unintentional mistake of my great-grandfather was his loud argument with Levashov. Vasily Stepanovich was outraged that he took someone else’s item without asking, and asked to return the scarf to its place. Having studied the case materials, it becomes clear that their relationship had been damaged for some reason for a long time. Levashov did not give the scarf back, he gave it to the party committee.

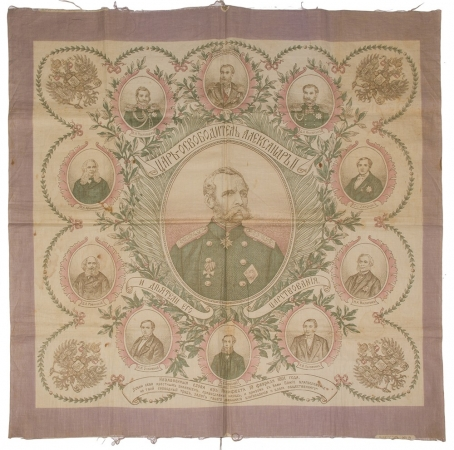

Family rumors were confirmed – the scarf had special features. It featured an image of Alexander II with inscriptions dedicated to February 19, 1861 – the abolition of serfdom. It was the scarf that became the reason for further proceedings.

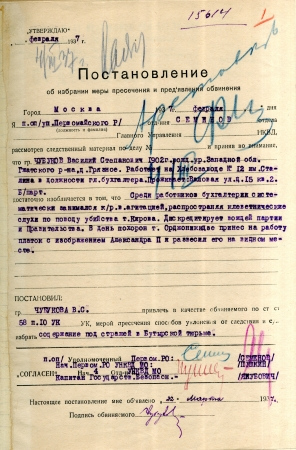

Vasily Stepanovich was arrested on March 7, 1937 on suspicion of counter-revolutionary activities, actually two weeks after the incident with the scarf. Two days before his arrest, a search was carried out at his residence address, but nothing interesting for the investigation was found.

After the arrest, new accusations and new witnesses to Vasily Stepanovich’s anti-Soviet activities suddenly appeared. Colleagues recalled many different situations. It turns out that back in 1934, my great-grandfather allowed himself to compare Stalin with the Tsar; after the murder of Kirov, he suggested that he was killed by his communist brothers; in 1935 he opposed cooperation; in 1936 he disrupted public meetings, for example to raise funds for women and children in Spain. But for some reason he continued to occupy a leadership position all these years…

I wrote down the names of everyone who participated in this case: both accusers and witnesses (there were 7 people in total). Not all participants gave negative characterizations. However, they took into account the most “important” testimony that allegedly confirmed guilt, for example Levashov, Gorelik, Novoselov. Yes, I do not deny that, being a relative, I want to brand, accuse, and make these names public, but from the position of a historian, everything must always be questioned. I do not know the circumstances that may have forced these people to give such testimony. All I have are pieces of paper with dry wording. In addition, I admit that my great-grandfather could have spoken sharply about some of the events that took place in our country. However, such carelessness also raises questions.

How to explain the scarf? No way. The person was in the way: extensive experience, good position, having his own opinion, perhaps some intransigence on certain issues. And if there is no person, there is no problem.

While studying the case, I discovered a pasted paper envelope in which evidence is usually stored. But there was only one piece of material evidence in the case. Handkerchief. It’s difficult to say exactly what feelings you experience when you have the opportunity to crumple in your hands a piece of fabric that has ruined the lives of several members of your family.

There was no scarf inside. It’s a pity. The archive employee said that the material evidence could not have just disappeared from them; it was in the form in which it was transferred to the archive.

I searched the Internet, and it turned out that now this kind of thing costs from 30,000 rubles. I think it’s ironic. This is what the scarf looked like, only “ours” had only Alexander II on it.

Vasily Stepanovich was convicted under the famous Article 58, paragraph 10 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR: “propaganda or agitation containing a call to overthrow, undermine or weaken Soviet power or to commit certain counter-revolutionary crimes, as well as the distribution or production or storage of literature of the same content entails – imprisonment for a term of not less than six months.”

The indictment states that Vasily Stepanovich partially admitted his guilt, which is at odds with the interrogation materials. 20 years later, during the rehabilitation process, there was no information about a partial confession: “Chubukov himself did not admit guilt.”

On June 14, 1937, a decree was issued with a punishment: 5 years in a forced labor camp. Vasily Stepanovich was sent to the North-Eastern forced labor camp, Sevvostlag, located in Nagaev Bay (now Magadan region).

After this document, until 1957, I know little about the life of Vasily Stepanovich. Unlike the future fate of his family.

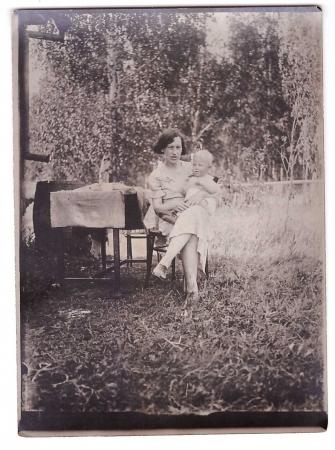

My great-grandmother, Irina Trifonovna Chubukova, disappeared from general family photographs in July 1937.

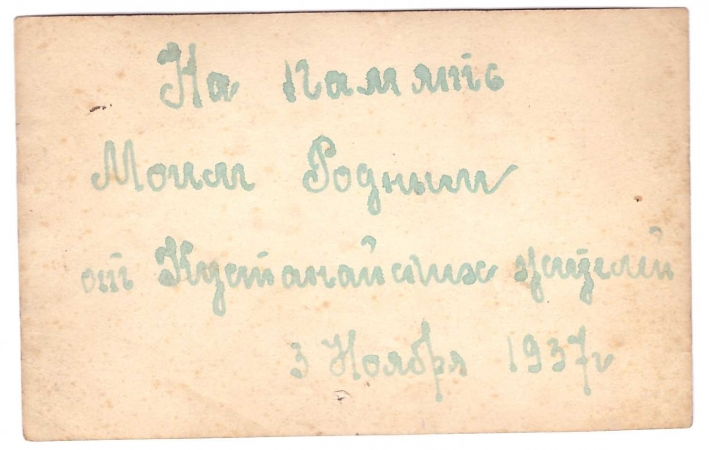

Suddenly my great-grandmother and my grandfather became the wife and son of an “enemy of the people.” I already know information about the next two years of Irina Trifonovna’s life from the words of relatives. The great-grandmother was deported to Kazakhstan along with the child. Photographs from the city of Kustanay date from November 1937 to the spring of 1938. Judging by the captions to the photo, she worked at a meat processing plant. According to my assumptions, Vasily Stepanovich’s sister, Maria Stepanovna Vasilyeva, about whom I know almost nothing, was also exiled with her.

There is a very interesting story connected with the deportation. In 1937, my grandfather became seriously ill with diphtheria. It is unknown when exactly this happened: during the journey to Kazakhstan or already there. As I understood from the stories, his condition was serious, and he was transported to Moscow to the family of his aunt, his great-grandmother’s sister. There he was raised as the youngest son until his mother returned.

Irina Trifonovna returned to Moscow to her son in the late 1930s or 1940. I only know that the divorce between my great-grandfather and great-grandmother was finalized in 1940. I hope that in the future I will be able to find out some details about her life during the period of exile. She never remarried.

Vasily Stepanovich served his sentence, and after his release from the camp he married a second time. The marriage produced two daughters. In the early 1950s, he visited Moscow, where he first saw his already matured son. In December 1957, Vasily Stepanovich was completely rehabilitated and moved to Moscow, where he lived until his death in the late 1970s – early 1980s.

My grandfather communicated with my father, but not as close as it could have been. Mom doesn’t remember Vasily Stepanovich well, but she still remembers his gifts, especially one of them – a wooden set of toy furniture from the Leipzig store.

I suspect that the status of “fatherless”, “son of an enemy of the people” did not pass without a trace for my grandfather. I think these things stay with you for the rest of your life in one form or another. How many such children were there in the territory of the former USSR? How many wives and sisters were deported? How many people were convicted under Article 58 for nothing?

After viewing these documents, I felt as if I had been hit on the head with something very heavy. This was my first case of a repressed person and it was immediately so personal. Later, as part of my duty, I will repeatedly work with similar cases with even more far-fetched and stupid accusations.

And I made an important conclusion for myself: we must not forget about this time, we must talk about it, talk about the people who suffered under the regime. If we do this, perhaps this will not happen again in our country.