A SPIEGEL column by Mikhail Zygar

Vladimir Putin has released 16 prisoners – Russians, Germans and Americans. That is a reason to celebrate. But thousands of others are still in prison and millions of Russians are suffering from the Stockholm syndrome.

August 2, 2024

In a month it will be exactly twenty years since a school was stormed in the Russian city of Beslan. More than 1,100 people – mostly children – were taken hostage. I have traveled to this school several times, I have walked through the gymnasium where the hostages spent three agonizing days.

I have spoken to many survivors: now that these children are adults, many of them can calmly remember and recount the heartbreaking details of this tragedy.

I often ask myself: What is it like to be held hostage for a long time and to live with the knowledge that you are a bargaining chip?

Today is a very happy day and a very sad day.

A happy day because so many hostages of the Putin regime have found freedom. I call them hostages deliberately – I think many of them were viewed as such.

I had no doubt that the US would not abandon its citizens Evan Gershkovich and Paul Whelan – but I did not expect their release to happen so quickly. My sources in Moscow did not believe that an agreement could be reached before the elections in November or even before the inauguration of the new American president in January.

I am very happy that the Russian hostages were also released, who were captured only because they are honest and fearless. They were against the war in Ukraine, they fought for freedom. Only a few days ago I was afraid that some of them might end their lives in prison.

We know very well that the negotiations began last year and that their goal was the release of Alexei Navalny. The Western negotiators knew that Putin wanted to free Vadim Krasikov, one of the most experienced assassins in the service of the Russian secret services, who was convicted in Germany for the murder of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in Berlin.

The negotiations were difficult. For example, the official Russian negotiators apparently did not dare to tell Vladimir Putin that the negotiations would also include the fate of Alexei Navalny (all other names were mentioned – but not the most important one). This is what an influential interlocutor in Moscow tells me.

Putin was ready to release both Whelan and Gershkovich, but he did not want to release the leader of the Russian opposition. He eventually killed him, it is said, to get him out of the current deal. This is why Navalny is currently lying in his grave and is not in Cologne, Germany, together with the other former prisoners from Putin’s prisons. Since Navalny’s murder, the negotiations have intensified, according to my information.

And, as one influential interlocutor in Moscow says: “It was politically more complicated for the Germans, but they negotiated much more intelligently than the Americans.”

Officially, FSB General Sergei Beseda and Yuri Ushakov, Putin’s foreign policy adviser, were responsible for the exchange on the Russian side; unofficially, Roman Abramovich, former owner of the London football club Chelsea and now de facto informal Russian foreign minister, was in charge, the only person in Moscow who can mediate between the West and the Kremlin.

Who has gained freedom through these efforts?

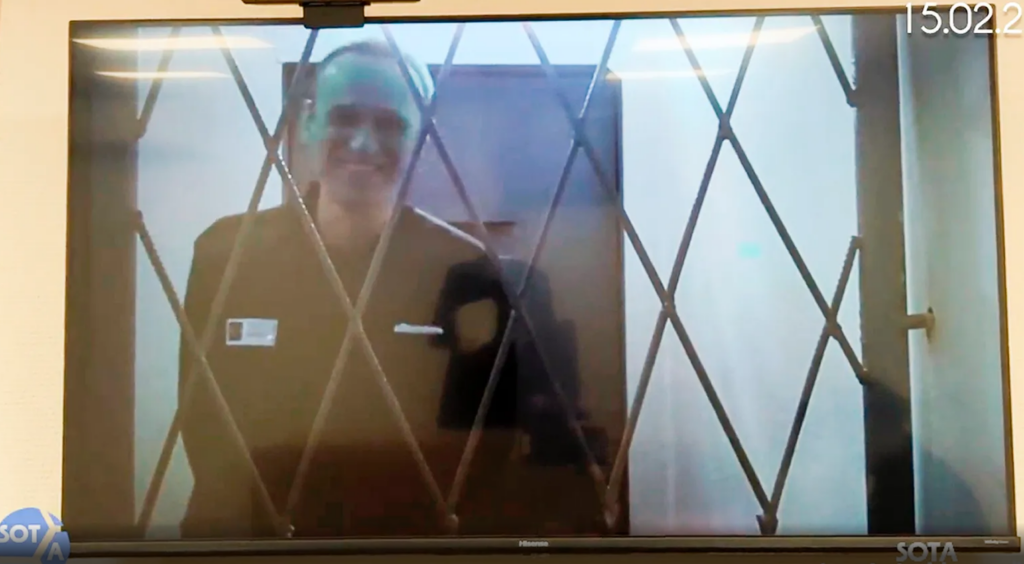

For example, 71-year-old Oleg Orlov, one of the legendary Soviet human rights activists and one of the leaders of Memorial, the organization that received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022. Orlov publicly described Putin’s regime as totalitarian and fascist – and was sentenced to two and a half years in prison for this this year.

Or Alexandra “Sascha” Skochilenko, a 33-year-old artist from Saint Petersburg. At the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, she did a small art project in which she replaced the price labels in a grocery store with anti-war slogans. For this, she was sentenced to seven years in prison. The time behind bars was a direct threat to her life: Sascha has a heart defect and bipolar disorder, and she could have died in a Russian prison.

Another example is the student Kevin Lick, a German citizen who is now 19 years old but was arrested as a minor. He was accused of taking photos of military equipment and sending them to someone in Germany. He was charged with treason. Apparently the Russian authorities themselves did not believe that the student could have been a spy – and so he was eventually sentenced to only four years in prison, usually in Russia there is much more for espionage. But we are talking about almost a child here.

And then there is Ilya Yashin, probably the best-known opposition figure in Russia, who was sentenced to 8.5 years in prison after the death of Alexei Navalny. Or Vladimir Kara-Murza, a publicist and politician who was sentenced to 25 years in prison for treason.

Liliya Chanysheva and Ksenia Fadeyeva, two young girls who were imprisoned only because they were regional activists and supporters of Alexei Navalny.

Today, all of them, Oleg, Sasha, Kevin, Vladimir, Ilya, Liliya, Ksenia and other hostages of Putin’s regime, are free again.

Even on a day like this, I have to think about the thousands of people who continue to sit in Putin’s prisons. About the poet Zhenya Berkovich. About the politician Alexei Gorinov, who protested against the war from the first day of Russia’s attack on Ukraine – and is now dying in prison. About Daniel Kholodny – the IT specialist who was put in prison for eight years for creating a website for Alexei Navalny. And about thousands of other people.

Yes, they are hostages too.

And I am sure that the majority of people living in Russia feel like hostages, even though they are not in prison. About 25 years ago, a gang of terrorists led by Vladimir Putin seized power in Russia. All these years they have terrorized the country’s population, thrown people into prison for any disobedience, accustomed citizens to the idea that resistance is impossible and pointless, and done everything to inflict Stockholm syndrome on Russians.

This thought often occurred to me when I was still living in Russia. And it occurs to me more and more often now.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, when Russia acquired new colonies in Siberia, the Caucasus or Central Asia, it was common to take “amanaty”. Usually these were children of local princes who were taken away from their parents and brought to Moscow or St. Petersburg for education. This was how the tsars wanted to secure the loyalty of the local elites. However, this was not a Russian invention. Iran and the Ottoman Empire also did this.

One of the most famous amanaty in Russian history is Jamaluddin, son of Imam Shamil, the leader of the anti-colonial struggle of the Chechens and Dagestanis in the 19th century. In 1839, Russian troops stormed Shamil’s capital, the rock fortress of Akhulgoo. The highlanders lost, and the imam gave his nine-year-old son Jamaluddin to the Russians as a hostage. However, this did not stop the Russians’ attack. Shamil’s sister and wife, as well as his newborn son and thousands of fighters were killed. Shamil escaped with a small group of followers.

Jamaluddin spent more than 15 years in Russia: he finished school and was drafted into military service. In 1855, during the Crimean War, Shamil took two Georgian princesses hostage, intending to exchange them for his son.

And the exchange took place. Jamaluddin returned to his father. At first he was very enthusiastic and proposed reforms that would improve the lives of people in Chechnya and Dagestan. He also insisted that his father make peace with Russia. Over time, both Shamil and all his relatives turned away from Jamaluddin. He seemed too pro-Russian to them.

After spending only three years in his homeland, Jamaluddin died of depression and (as was believed at the time) tuberculosis.

People who are held hostage for a long time change. They acquire new character traits, new qualities, new views on life.

In 1917, Russia was taken over by a group of Bolshevik terrorists led by Lenin. The Red Terror they unleashed changed Russia completely. What we see in Russia today is a result of that seizure of power. The Soviet mentality, the longing for empire – all these are traumas that many have taken with them from decades of Soviet rule. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the hostages were released – but a new gang of terrorists managed to take power again.

It is a happy day, but it is also a sad day.

It is very difficult to help the millions of Russians who feel held hostage by Putin. It is impossible to exchange millions of people. Even if a few heroes have gained their freedom, we must remember that thousands of other hostages are sitting in Putin’s prisons.

Over the years, Putin has successfully turned the entire country into a gulag. He is thereby destroying the lives of new generations.