80 years ago, Hitler and Stalin divided Eastern Europe between themselves. Now the fateful agreement is to be rehabilitated in Russia. Why?

Spiegel article by Christian Neef

August 16. 2019

It is Sunday, December 24, 1989, when the chairman of the Congress of People’s Deputies in Moscow calls the deputies to the final vote. There is a tumult in the Kremlin’s Congress Palace – the 2,250 deputies of the parliament, which had been freely elected for the first time a few months previously, are to decide on a text that has been the subject of dramatic wrangling in the days before.

The bill is numbered 979-1 and is called “Political and legal assessment of the Soviet-German non-aggression pact of 1939” – a treaty that most people know as the Hitler-Stalin Pact. The deputies are to decide whether the agreement was legal or a breach of international norms.

Anyone who grew up in the Soviet Union must find this outrageous. For 50 years, the Communist Party had celebrated the non-aggression pact of 1939 as the highest art of Soviet diplomacy because it supposedly delayed the war with Germany. Moscow kept the rest of the agreements secret protocols in which Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin defined spheres of interest secret or described them as forgeries.

Politburo member Alexander Yakovlev, one of Communist Party General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev’s closest confidants, is standing at the lectern. Stalin made common cause with Hitler in 1939 in a morally untenable way, says Yakovlev. He spoke to his neighbors in the language of ultimatums and threats, divided Poland together with Hitler, and ruthlessly Sovietized the Baltic republics. This undermined state morality. “The secret protocol of August 23, 1939 reflected the inner core of Stalinism,” he explains. “It is not the only one, but one of the most dangerous mines with long-term effects in the minefield that we inherited and now have to clear with such great effort and difficulty.”

Putting an end to the taboos of the Soviet era is the aim of perestroika under reformer Mikhail Gorbachev. Soviet history is also being examined. The day before, there was already a first vote on this topic – it had gone wrong, the doubts about the existence of the secret protocols were too great. Yakovlev then called together experts for a night-time crisis meeting and presented notes from a Kremlin archivist on December 24th. They testified that the protocols really did exist and that the Soviet leadership had the originals removed from the archives after the war.

This is the breakthrough. The draft receives more than half of the votes: 1,435 MPs present vote for the resolution, 251 are against, 266 abstain – a hard-won victory for the liberal forces. Gorbachev looks tensely into the hall. He probably suspects that the reassessment of the Hitler-Stalin Pact will be the turning point of his perestroika and that the Soviet Union – as it exists now – will hardly survive.

The document that has now been adopted states that Stalin and Molotov conducted the negotiations with Germany on the secret protocols without informing the Soviet people, the party leadership, the parliament and the government of the USSR. “The signing was an act of personal power and did not reflect the will of the Soviet people. The Congress considers the secret protocols legally irrelevant and invalid from the moment of their signing.”

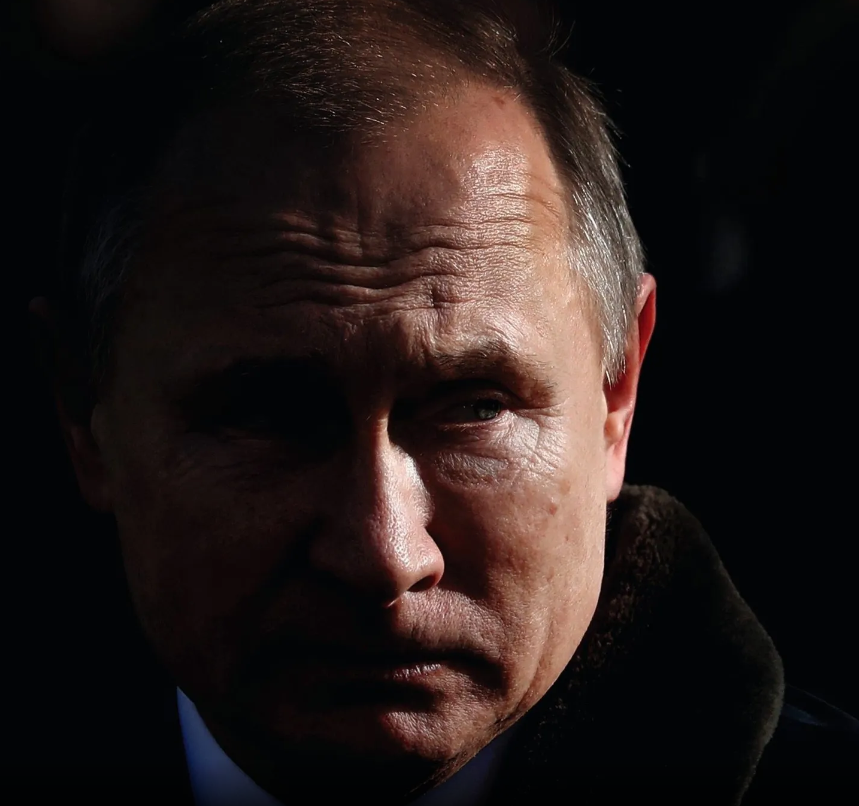

80 years have passed since the signing of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, almost 30 since that vote in the Kremlin Palace. Anyone who thinks that there is hardly anything left to say on this topic is far from it: Just in time for the 80th anniversary of the agreement that German Chancellor Helmut Kohl once called, like others before him, the “devil’s pact”, resistance is stirring in Russia against the assessment made under Gorbachev. It is a debate that must be taken seriously. It is more than a historical trifle or Stalin nostalgia, nor is it an internal Russian matter. It is aimed at Russia’s handling of international law and affects current world politics. The pact still influences the geopolitical realities in Europe today.

The debate was launched in March in the Moscow newspaper “Izvestia” by Mikhail Myagkov, the scientific director of the Russian Military History Society. It was founded in 2012 by a decree from President Vladimir Putin and is intended to “counter the distortion of Russian military history”. It is chaired by Putin’s Minister of Culture, and its members include ministers, entrepreneurs close to the Kremlin, scientists and well-known representatives of the Russian elite.

In the West, the number of comments blaming Moscow for the agreement with Hitler – and thus for unleashing the Second World War – is growing at the “speed of a falling snow avalanche”, says Myagkov. It is time to stop “throwing ashes on our heads”, says Myagkov. It is worthwhile “for Russia and above all for the members of the State Duma to revise the accusatory resolutions that were passed at the Congress of People’s Deputies in 1989”. It is an unvarnished call to parliament to overturn the condemnation of the pact from the Gorbachev era.

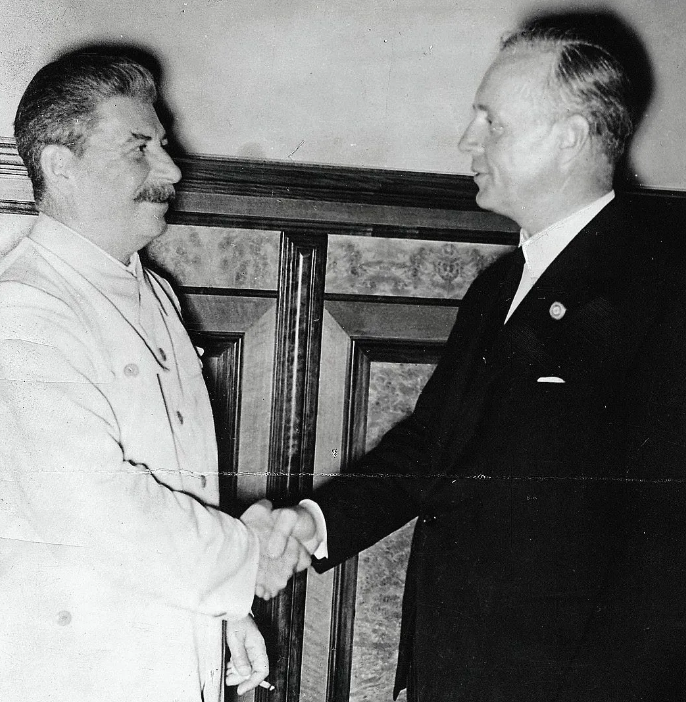

If you walk through Moscow today and look for traces of those dramatic days in August 1939, when Hitler’s Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop was in the Soviet Union to sign the pact, you will hardly find any. The old airport on the former Leningrader Chaussee no longer exists. Ribbentrop and his delegation landed there in the early afternoon of August 23rd in two Focke-Wulf Fw-200 “Condor” aircraft. Hardly anyone knew anything about the arrival of the German delegation, and those who heard about it could hardly believe it.

Negotiations began on August 23, 1939 at 6 p.m. in the office of Ribbentrop’s counterpart, Vyacheslav Molotov. Molotov, head of government since 1930, had also been appointed foreign minister a few months earlier. Ribbentrop realized that he was of secondary importance in the negotiations when he was surprised to see Stalin standing in Molotov’s office.

The situation on the continent was at breaking point. In 1938, Hitler had incorporated Austria into the German Reich, annexed the Sudetenland and, with an ultimatum in March, also taken back the Memel region. Now he was planning to invade Poland. The first major war on the continent since 1918 was looming. France and Great Britain issued a guarantee for Poland’s independence and also began to negotiate a military agreement with Stalin. This seemed to convince Hitler of the need to secure Soviet backing before he began the war against Poland at the end of the summer.

At the end of July he decided to seek an understanding with the Russians. Shortly afterwards Ribbentrop informed Molotov that if they met he could sign a protocol that would regulate the spheres of influence of both sides in the Baltic region. It was a barely concealed hint that the Baltic states would be handed over to the Soviet Union.

On August 19, Molotov presented the German ambassador with a draft of a non-aggression pact. On the 21st, Stalin agreed to Ribbentrop’s trip to Moscow. According to Legation Counselor Gustav Hilger, who was interpreting during the negotiations, Hitler received the news with impetuous joy: “Now I have the world in my pocket!” he is said to have shouted and pounded against the wall with both fists. France and England, whom the Kremlin leader trusted far less than Hitler, were thus out of the running. On the 23rd Ribbentrop faced the leader of the Soviet Union. The negotiations went smoothly.

The non-aggression pact, which was signed long after midnight but was dated August 23, was valid for ten years and obliged both sides to refrain from attacking each other and not to support any third power that might attack their partner. This made it clear that Hitler would have a free hand in Poland.

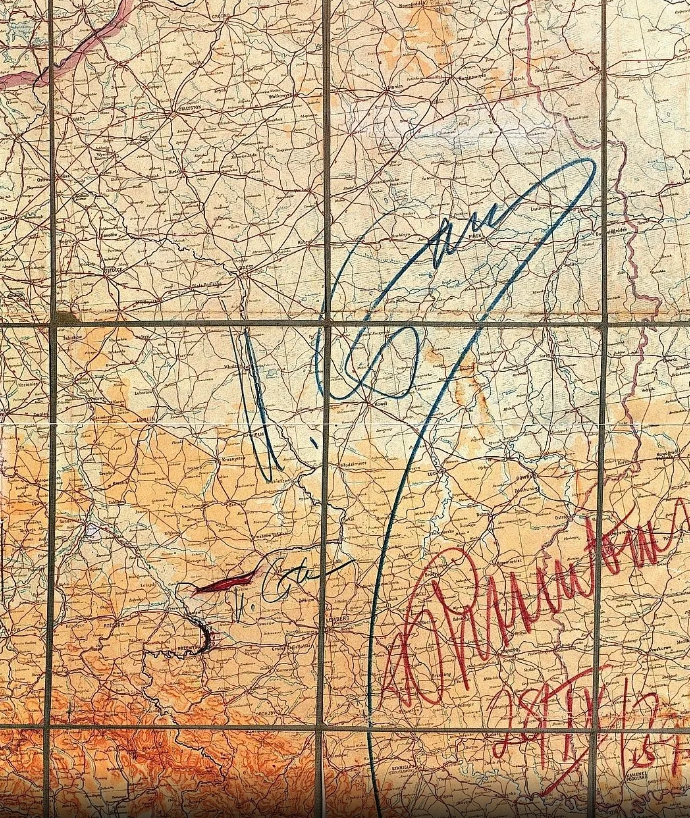

However, the secret additional protocol, which Stalin attached great importance to, was much more far-reaching. According to it, the line between the German and Soviet spheres of interest in the Baltic region would run along the northern border of Lithuania and in Poland would follow the course of the Narew, Vistula and San rivers. When Ribbentrop flew to Moscow again in September and signed a border and friendship treaty with Molotov, Lithuania was included in the Russian sphere of influence at Stalin’s request. In return, Hitler received the Lublin region and part of the Warsaw region.

Stalin himself signed the new dividing line between Germany and the Soviet Union on a map with a thick blue pen: from the southern border of Lithuania to Czechoslovakia. It is an undignified haggling between two dictators who are hawking off the property of their small neighbors, and doing so in the best of spirits. At times he almost believed he was “among old party comrades,” said the Danzig Gauleiter, who accompanied Ribbentrop, on the return flight. And indeed: Stalin was quite impressed by Hitler at this time, and he even considered a meeting “between the Führer and me” to be “desirable and possible.”

The consequences of the secret protocols are fatal and cost countless people their lives. On September 1, Hitler’s troops march into Poland. On September 17, at five in the morning, Stalin’s soldiers. While the Wehrmacht crushes Poland from the west, 28 rifle and 7 cavalry divisions, 10 tank brigades and 7 artillery regiments of the Red Army occupy the east of the country. Stalin sends 466,000 men with 4,000 tanks and 5,500 guns as well as 2,000 aircraft to Poland. He occupies 52 percent of Polish territory with a population of more than 13 million people. Almost 330,000 people are deported to Siberia or Central Asia.

The following year, Stalin also takes over the Baltic countries, after forcing them to sign mutual assistance agreements through sheer blackmail. The valuable strategic positions on the Baltic Sea fall into Stalin’s lap without a fight. Tens of thousands are deported.

The effects of the pact also include the tragic fate of several hundred German anti-fascists, communists and Jews who fled to the Soviet Union to escape the Nazis. After the pact was signed, Moscow handed them over to the Hitler regime at the Soviet border. Many of them, including the partner of the top KPD official Heinz Neumann, who was shot in the Soviet Union, ended up in concentration camps.

When Hitler invades Poland, it seems as if he is doing so at Stalin’s invitation. France and Great Britain come to Poland’s aid and declare war on Hitler’s Germany. Stalin’s Foreign Minister Molotov comments on their decision before the Supreme Soviet as follows: “It is not only senseless, but also criminal to wage such a war as a war to destroy Hitlerism”: Hitler wants to end the war as quickly as possible, Great Britain and France do not want that – they are the real warmongers.

After the war, Stalin has argument aids made so that his image as the most important anti-fascist in the world is not further tarnished. The pact is praised as a brilliant move. Without it, one argument goes, the USSR would have become the victim of a crusade by the capitalist states. But in this way it bought itself a two-year respite before Hitler – despite the non-aggression pact – invaded the Soviet Union. During these two years, they were able to prepare for war – an argument that is nonsense, because Stalin was completely surprised by Hitler’s attack in 1941 and his army went into a catastrophic defensive.

The headquarters of the Russian Military History Society is in an old palace in Moscow’s Petrovsky Lane, which was built after Napoleon’s invasion in 1812. It exudes dignified elegance. Mikhail Myagkov, a specialist in the history of the Great Patriotic War from 1941 to 1945 and a professor at the diplomatic training school MGIMO, receives us in his office. Yes, he is in favor of reviewing the decision on the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1989, he says. This follows “logically from the dynamics of historical consciousness.” The decision at the time was made during perestroika, at the height of the mood that only viewed the Soviet Union negatively. “The deputies were under pressure from an aggressive minority of the Baltic republics that had gathered in Moscow. They wanted revenge for what they called the ‘occupation’ of the Baltic countries by the Soviet Union. However, the annexation of the Baltic states, which took place after the pact, was something that a large part of the population wanted. How can you call that ‘occupation’?”

Then Myagkov gets to the real point: “The Baltic independence leaders initiated the condemnation of this pact in 1989 in order to break their countries out of the Soviet Union. They were the trigger, they brought down the national pillars of the Soviet Union.” The liberal majority in Russia at the time greeted this with enthusiasm.

Myagkov stresses that this is his personal opinion. But he has prominent support, not only from Duma deputies, but also from former Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov, who was head of the presidential administration for five years under Putin and is now chairman of the board of trustees of the Military History Society. He has been appearing in interviews and press conferences for weeks.

As the legal successor to the USSR, Russia has “in any case the possibility” to decide on the annulment of the decision from the Gorbachev era, says Ivanov. “In the 1990s, he contributed to our diplomatic, ideological and de facto disarmament vis-à-vis the West.” This means that the agreement between Stalin and Hitler must be stripped of its negative reputation.

In the press and on television, Myagkov, Ivanov and other supporters of a historical revision are now spreading arguments in favor of the pact. They emphasize that other states have made similar agreements with Hitler and that secret protocols were sometimes part of these pacts. The Supreme Soviet only ratified the non-aggression pact, not the secret protocols. Legally, they therefore never existed.

As far as territorial conquests are concerned, Stalin only took back those areas that had once belonged to the Soviet Union or Russia anyway, say Myagkov and Ivanov. France did the same with Alsace-Lorraine. In addition, the Soviet Union had to protect the Belarusians and Ukrainians who lived in eastern Poland at the time. These are similar arguments to those Putin used in 2014 when he “brought home” Crimea.

This is also one of the explanations why the Moscow leadership wants to reassess the Hitler-Stalin pact. It wants to build on the great old Russia.

However, the pact’s apologists are silent about one thing: how ruthlessly the Soviet Union acted in Poland. Ivanov says that Moscow had no choice but to invade Poland. The country had already collapsed at that point, the army was in agony and the government was on the run – Poland de facto no longer existed. Not a word about the fact that the Soviet Union gave Hitler the necessary backing during his invasion.

Vladimir Putin also described the pact as “morally unacceptable” in 2009. But he is a master of ambiguity when assessing Russian history – and has now relativized his own judgment. In 2014 he declared: “People say: Oh, how bad this (treaty) is. But what is bad about it if the Soviet Union did not want to fight (against Hitler)?”

What do those who are accused of the 1989 resolution being a provocation by anti-Soviet forces say? Mikhail Gorbachev, now seriously ill, says he has not changed his mind – he voted to condemn the pact. Most of the members of the commission that studied the 1939 archive documents and drafted the resolution are already dead. Among the few still alive is the writer Vitaly Korotich, once editor-in-chief of the magazine “Ogonyok” (The Little Flame), which, with its five million copies, was the most popular paper of perestroika. Korotich, now 83 and Ukrainian, represented Estonia on the commission.

The pact placed a bomb under the foundations of the Soviet Union that was bound to explode sooner or later, says Korotich in his apartment in Moscow. Stalin used force to incorporate western Ukrainians and Balts, who had a completely different mentality to the Russians. The line that Stalin and Hitler drew in 1939 to demarcate their spheres of power still pulsates today, and it emits a dangerous radiation. “The hatred of Russia is building up along this line.”

In fact, 80 years later, the border line once drawn by Stalin has become an extremely sensitive geopolitical area. Today, the division of Europe runs along it, no longer along the Elbe and Saale. The region of former Bessarabia is now home to the more western-oriented Republic of Moldova – Russia is supporting the small separatist republic of Transnistria, which has broken away from Moldova, with soldiers and weapons. Western Ukraine, on the other hand, is a red rag to the Kremlin – hardly a day goes by without Moscow media reporting on “fascist” activities in the region. “Annexing western Ukraine was Stalin’s biggest mistake,” believes Korotitsch. “It has always belonged to Poland or Austria-Hungary, it has a different religion, a different dialect. Without it, the Maidan would never have happened.” The uprising that led to the fall of the pro-Russian government of Viktor Yanukovych in 2014 came mainly from the west of the country.

Relations between Poland and Moscow have even worsened in recent years. And the Baltic states? The Kremlin is using the Russian minorities living there as a fifth column to defame Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. The reactions are accordingly harsh. Poland and Ukraine are convinced that the Hitler-Stalin pact led to the unleashing of the Second World War.

For Korotitsch, reassessing the 1939 pact would be an act of revanchism. “When people in Germany fight to bring back Danzig or Königsberg, they are considered crazy or condemned. Here, the head of the secret service can say that there was no terror under Stalin and that we reintegrated our own territories in 1939 – and nobody condemns them for it.”

Even the men and women who forced the vote on the secret protocols in 1989 are now hard to find. In Vilnius, Lithuania, you can at least meet music professor Vytautas Landsbergis, former leader of the Lithuanian independence movement and the first acting head of state of this Baltic republic.

He is now 86, his office is in a residential area in the north of the city. Behind him, witnesses of the past hang on the wall: Landsbergis in photos with George Bush, with Helmut Kohl and Margaret Thatcher, with Reagan and Mitterrand. Vytautas Landsbergis was once the hero of the Baltic states. He helped organize the human chain for independence and stood firm in January 1991 when Soviet tanks tried to bring the Lithuanians to their knees once again. On the so-called Vilnius Bloody Sunday, 14 people were killed and more than a thousand injured.

Landsbergis tells how much even Gorbachev maneuvered in 1989. “He and his entourage did not want to annul the pact, but only condemn some of its details – in order to preserve the old empire. But the Russian democrats supported us, especially Yeltsin and Sakharov. And so the whole debate slipped out of their hands.” The Soviet Union had to answer the question at the time about its relationship to Stalin’s crimes, says Landsbergis. “If they now say in Moscow that the 1989 decision was unlawful, Hitler will send them congratulations from his grave in hell.”

Landsbergis says that in 1989 the Baltic states were not concerned with condemning Russia, but with restoring justice. “We entered the Soviet Union through betrayal and violence. The fact that the Lithuanian people asked to join is Moscow propaganda. Did we put the noose around our own necks and beg for hundreds of thousands of people to voluntarily go to Siberia? They always lie in the same way. Then as now. In 2014 they said that their soldiers were not in Crimea, that they were green Martians.”

Did the Hitler-Stalin Pact lead to the outbreak of World War II? There is no yes or no answer to that. One thing is certain: Stalin paved the way for Hitler because his interests coincided with those of Hitler. Both wanted to destroy Poland. The outbreak of war was a matter of time after the pact was signed. It is also not true to describe the treaty with Hitler as having no alternative from Moscow’s point of view. The USSR could have remained neutral in 1939.

Until recently, few would have thought that the story of the Hitler-Stalin Pact would not only continue to stir up emotions, but would also reveal new things even decades later. A few years ago, the diaries of Ivan Serov, the first chairman of the KGB, were found. Serov had been appointed deputy head of the Main Directorate for State Security in the summer of 1939. On August 23, Stalin’s Minister of Defense ordered him to secure Ribbentrop’s flight to Moscow. He was to ensure that the air defense regiment stationed in Bezhetsk, which had no knowledge of the Germans’ overflight, did not shoot at their planes.

Serov arrived in Bezhetsk on time, but for some reason one of the batteries actually fired at Ribbentrop’s two planes. Serov immediately rushed back to Moscow and inspected the German planes parked at the airport. To his relief, he found no bullet holes in the fuselage or wings. The commander of the regiment and the chief of the battery that opened fire were nevertheless brought before a military court.

If Ribbentrop had been accidentally shot down by the Soviets that day, would the Hitler-Stalin pact never have been made?

Mikhail Myagkov, the director of the Russian Military History Society, is fairly certain about the answer to this question: “There would have been no rift between Germany and the Soviet Union. Hitler would have sent a new foreign minister. The pact would have been made in this case too.”