Film critical of Stalinist times. By Tengiz Abuladze.

First banned in the Soviet Union, under Gorbachev briefly allowed

Wikipedia

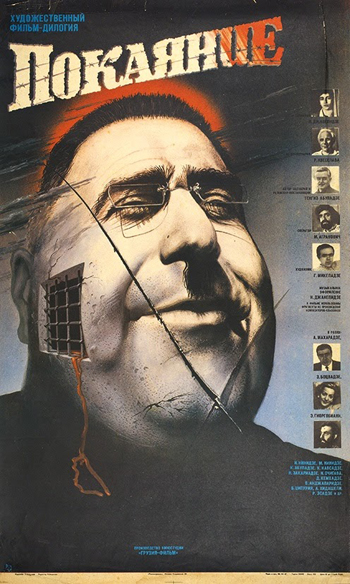

Repentance (Georgian: მონანიება translit. Monanieba, Russian: Покаяние) is a 1984 Georgian Soviet art film directed by Tengiz Abuladze. The film was produced in 1984, however, it was banned from release in the Soviet Union for its semi-allegorical critique of Stalinism. It premiered at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival, winning the FIPRESCI Prize, Grand Prize of the Jury, and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. The film was selected as the Soviet entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 60th Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee. In July 2021, the film was shown in the Cannes Classics section at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival.

Availabe on YouTube:

Repentance (episode 1) (1984)

Repentance (episode 2) (1984)

Total running time for entire film: 153 minutes

Plot

Repentance is set in a small Georgian town. The film starts with the scene of a woman preparing cakes. A man in a chair is reading from a newspaper that the town’s mayor, Varlam Aravidze has died.

One day after the funeral the corpse of the mayor turns up in the garden of his son’s house. The corpse is reburied, only to reappear again in the garden.

A woman, Ketevan Barateli, is eventually arrested and accused of digging up the corpse. She defends herself and states that Varlam does not deserve to be buried as he was responsible for a Stalin-like regime of terror responsible for the disappearance of her parents and her friends.

She is put on trial and gives her testimony, with the story of Varlam’s regime being told in flashbacks. During the trial, Varlam’s son Abel denies any wrongdoings by his father and his lawyer tries to get Ketevan declared insane.

Varlam’s grandson Tornike is shocked by the revelations about the crimes of his grandfather. He ultimately commits suicide. Abel himself then throws Varlam’s corpse off a cliff on the outskirts of the town.

At the end, the film returns to the scene of the woman preparing a cake. An old woman is asking her at the window whether this is the road that leads to the church. The woman replies that the road is Varlam Street and will not lead to the temple. The old woman replies: “What good is a road if it doesn’t lead to a church?”

Two Reviews from the 1980s

‘REPENTANCE,’ A SOVIET FILM MILESTONE,

STRONGLY DENOUNCES OFFICIAL EVIL

A New York Times Review

By Felicity Barringer

November 16, 1986

”I made the film so that this would never happen again.”

With those words, spoken in firm but unemotional tones, the Soviet film director Tengiz Abuladze explained the genesis of ”Repentance,” the first Soviet film ever to give a sweeping and frank portrayal of the madness that gripped the country during the purges of Josef Stalin.

”You just don’t see these things here,” one Soviet man said after attending one of the recent private showings in Moscow. At the film’s end, a long moment of silence was followed by an unusual burst of fierce applause. The film, made for but never shown on television, is expected to open at theaters nationwide late in 1986 or early in 1987. Mr. Abuladze said it may be entered in the next Cannes Film Festival.

Even taken outside the context of the Soviet Union, ”Repentance” is a strong emotional denunciation of official evil. It melds reality, allegory, hallucination and grotesque fantasy to describe a totalitarian dictator and a society out to destroy not just its people but its past. Then Mr. Abuladze uses the same techniques to show how the dictator’s heirs hide his crimes and live off the fruits of his pillage.

But in this country, where literature and, in the 20th century, film, have very often been powerful vehicles of social criticism – and where works and their creators have often been suppressed – ”Repentance” is both a cultural and political milestone.

Some Muscovites liken its appearance to the publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s ”One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,” the story of Stalinist labor camps whose appearance in 1962 marked the beginning of a short-lived period of cultural liberalization here. It is one of the most daring creative works to appear in the Soviet Union since Mikhail S. Gorbachev took power here 20 months ago and beagn to call for ”openness” (”glasnost”) in the nation’s cultural, political and economic life. Thus far, it is the cultural and literary segment of this traditionally cautious society that has come closest to taking Mr. Gorbachev at his word.

The film stops short of actually mentioning Stalin or showing his picture. Its chief villain is Varlam, a madman-dictator with a mustache vaguely like Hitler’s, a love of pomp and opera much like Mussolini’s, and the mincing pince-nez and bull neck of Lavrenti Beria, the head of Stalin’s secret police.

”The essence of this film is that this might happen at any time and in any country,” the 62-year-old Mr. Abuladze said in a recent interview. But the fictional town where the film is set is clearly a part of Soviet Georgia, the native republic of Stalin, Beria and Mr. Abuladze. The stories of the film’s victims are drawn from the history of well-known Georgian cultural and political figures who were arrested and shot in 1937, Mr. Abuladze said.

The film breaks one taboo with its emotional depiction of persecution, false arrest, torture and false hopes. Then it goes on to break another taboo, condemning, by implication, the generation that came after the dictator Varlam.

”How long will you lie?” Varlam’s son is asked by his own son, a teenager horrorstruck by the revelation of his grandfather’s deeds. As if to underscore the link between the overt sins of Varlam the father and the covert ones of Avel his son, Varlam and Avel are played by the same actor, Avtandil Makharadze.

For two years Soviet censors suppressed the film ”Repentance” (”Pokayaniye” in Russian), but this past summer, 15 months after Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, a dramatic change of the guard took place at the Union of Cinematographers. Mr. Abuladze’s friend Elem Klimov took charge.

Mr. Klimov set up a committee to review banned films, allowing the old works of the emigre director Andrei Tarkovsky back on the screen and resurrecting other films that have been censored for 15 years or more. After it was reviewed, ”Repentance” started being shown to overflow audiences at theaters in Tblisi, the capital of Georgia.

Last month, Mr. Abuladze said, one of the four existing copies of the film was brought to Moscow for showings to select audiences – the only copy with a Russian voice-over translation of the Georgian-language soundtrack. Word of the film’s power spread rapidly; one unadvertised showing, whose sponsors got the copy of the film barely two hours before the lights dimmed, still attracted knots of young people asking in vain for ”spare tickets.”

Well-informed sources in the cultural world say that the film’s nationwide distribution was approved by two members of the ruling Communist Party politburo, Yegor K. Ligachev, the ideological chief, and Aleksandr N. Yakovlev, chief of Soviet propaganda.

In a recent interview about the film and its release, Mr. Abuladze quotes the 19th-century Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, saying, ”Silence will not cure a disease. On the contrary, it will make it worse.”

Many of Mr. Abuladze’s earlier works, like the film ”Entreaty” (”Molba” in Russian), are based on the rich Georgian literary tradition, which dates back even further than the Russian tradition. But Soviet intellectuals say that the images in ”Repentance” are borrowed from a newer literary vein, the underground literature that sprang from Stalin’s labor camps. Most of these works were never published, but manuscripts, called ”self-published” or samizdat, were widely circulated.

”This film,” said the dissident Soviet historian Roy A. Medvedev, ”is the beginning of the second generation of literature about the Stalin period,” incorporating the literature of the first generation. A Moscow filmmaker told Mr. Abuladze, ”After this we will have a whole new literature.”

The movie is redolent with snippets of fact from the Stalin period. Its opening scene shows a woman -later revealed to be the daughter of one of Varlam’s victims – making confectionery churches when she learns of Varlam’s death. In fact, a prominent Georgian Communist, Mamiya Orakhelashvili, was executed in 1937 and, Mr. Abuladze said, the man’s daughter worked in a bakery until the end of her life.

In the film, the baker’s father, arrested, tortured and killed by Varlam, is an artist, Sandro, who first attracts the dictator’s attention by petitioning him to remove electrical equipment from the town’s catherdral, its leading cultural monument. The next day, two members of the delegation are arrested. Mr. Abuladze said such a delegation went to Beria, who agreed with their petition, and a day later had three of them arrested.

But the material based on Georgian history, powerful as it is, is eclipsed by the scenes that come from the literature of the labor camps. After Sandro’s arrest, his wife and daughter join a long line of women going to a small booth to seek the addresses of their arrested husbands – an image strongly reminiscent of the poem ”Requiem” by Anna Akhmatova, whose husband was killed in the purges.

The women are given the same answers that the secret police gave in the 1930’s. To hear the words ”sentenced to 10 years’ exile without right of correspondence” was to know that a death sentence had already been carried out by a firing squad. ”Package received” meant a prisoner was alive.

At another moment, during Sandro’s surreal interrogation, done in a garden by a man in a tuxedo, another victim, Sandro’s friend and mentor Mikhail, is brought in. Mikhail then betrays Sandro, naming him as part of an absurd conspiracy of 2,600 men who were going ”to dig a tunnel from Bombay to London.”

Justifying his betrayal to Sandro, Mikhail uses the same logic one prisoner and betrayer describes in Alexander Ginzburg’s book on the Stalinist camps, ”Blind Route.” ”It’s madness,” Mikhail says. ”I said it because it is obviously madness. Everybody can’t be guilty. They can’t arrest everybody. . . Understand, Sandro, it’s a stratagem.”

Such a stratagem is obviously doomed. Varlam himself accepts the work of one zealous henchman, who arrests not just one designated victim but 35 people with the same surname. Proud of his work, the man says to Varlam, ”Look, I’ve brought you a whole carload of enemies of the people.”

As shocking as some of these scenes are, allusion to kangaroo courts and false confessions has been made in other recent films, particularly the 1984 film ”Scarecrow,” in which vindictive young adolescents persecute a girl who comes from an obviously intellectual household, and the girl, to save a friend, confesses to something she didn’t do.

But the second element of the film – the evil of keeping silent about evil – may never have been so clearly stated in a Soviet film. While the film tells the story of Varlam’s crimes through the words of the female baker, it condemns the lies through the anger of Varlam’s grandson Tornike.

The baker has gone on trial for repeatedly exhuming Varlam’s corpse, and her trial testimony is heard by a group of Varlam’s old retainers and by his family. After the judges decide to commit the woman to an insane asylum – obviously to silence her -Tornike confronts his father, Avel, asking him to explain Varlam’s deeds.

”It was a difficult time,” says Avel. ”Your grandfather was trying to build a better world for everyone. . . . What’s one life, when you’re trying to build a better world for everyone?’‘ And then, in an almost pleading scream, ”He didn’t kill anyone with his own hands.’‘

”The image of Varlam is so generalized, it’s like a mask of evil,” Mr. Abuladze explained. ”His son is more frightening, a more difficult character.” Pointing out that many of those attending the film in Tblisi were young, more Tornike’s contemporaries than Avel’s, he said, ”Young people are attracted by the themes of fathers and sons, of fathers who stick to the old ways and, as the youth think, lie all the time.”

Mr. Abuladze shrugged when asked why Stalin’s name was not used in the film. Then he said, ”There are many characters like that [ Stalin ] who are not named. It’s impossible to gather evrything in one film.”

”But Stalin is a presence?” he was asked.

”Everybody is a presence. Not just Stalin. All those who abused their power.”

When asked why his film was kept on the shelf for two years, Mr. Abuladze smiled and said, ”You know about wine, don’t you? Good wine needs time to mature.” At another point, he said, ”Sometimes artists are a little ahead of their times.”

But it is the political vacabulary of Mr. Gorbachev’s government that Mr. Abuladze falls back on when describing the purpose of his film. ”We are supposed to be telling truth, truth, all the time truth,” he said.

The film’s female baker, who, in the grotesque early scenes, repeatedly exhumes Varlam’s mouldering corpse and leaves it in Avel’s garden, says at her trial, ”I will do it again. To bury him is to bury what he did.”

In the film, Varlam clearly accepts and relishes the evil of his actions. But Avel, who at one point descends to a basement filled with Sandro’s stolen paintings and tries to confess before Sandro’s stolen Crucifix, is told by a demonic figure near him, ”You’re not repenting, you’re coming here out of fear.”

At the film”s climax, Tornike confronts his father and says, ”At least my grandfather’s conscience troubled him. But you have no conscience.” Despite the film’s name, Tornike is the only character to show any true repentance for what has happened. And Tornike, after the final denunciation of his father, shoots himself with the gun Varlam gave him.

REPENTANCE (1984)

Turner Classics Movies Review, n.d.

By Rob Nixon

A decade or more before its completion in 1984, Tengiz Abuladze’s powerful political film Repentance would have been unthinkable in the Soviet Union. Even in the more relaxed and open climate of the perestroika/glasnost era in the second half of the 1980s and with support from high officials, notably Eduard Shevardnadze and Mikhail Gorbachev, the film had its difficulties and would not be widely released for three more years, premiering at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival.

Georgian filmmaker Abuladze’s attack on Stalinism and its heirs incorporates surreal touches and moments of dark humor into a parable of the evils of tyranny. The story follows events after the death of the mayor of a small Georgian town, Varlam Aravidze, a man responsible for a lengthy Stalin-like reign of terror in the town. A day after the funeral, Aravidze’s corpse appears in the garden of his son’s house. It’s reburied, only to turn up again, leading to the arrest of a woman who says he has no right to burial because of his past actions. At her trial, the story of Aravidze’s regime is told in flashbacks.

Abuladze began his career in the 1950s, making 11 documentaries, TV movies, shorts, and features through the mid 70s. Following a near fatal car accident and months of recovery in hospital, he set out in 1981 to write “something that really mattered; something important.” The script was ready in 1982, and although it was sharply critical of Soviet rule, he was sure he could get it made. The script was sent to Shevardnadze, then head of the Georgian Communist Party and later Minister of Foreign Affairs under Gorbachev. Shevardnadze liked it and made some suggestions, but because no picture could be made without the approval of the Soviet film council Goskino, Abuladze decided to make Repentance under a rule that authorized Georgian television to produce a single cultural program annually, pending approval of its theme by Moscow. Permission was granted based on a single telegram drawing on the director’s reputation: “Tengiz Abuladze will shoot a program on a moral-esthetic subject.” The movie was shot in five months in 1984 using Georgian artists and actors, many of them his friends and family.

Repentance was delivered to Goskino on Christmas that year and shelved for nearly two years. Abuladze refused to make any changes, firm in his belief the story would one day be seen widely. Eventually, Gorbachev saw the film and liked it, as did Minister of Culture Aleksandr Yaklovev, who sent it to Cannes. The movie was cleared for exhibition in the USSR in the more open atmosphere of the final years of Communist control, and international distribution followed shortly after, almost unheard of for a Georgian-made motion picture. Such was the success of the production that Abuladze was asked to accompany Gorbachev on his first official visit to New York in 1988. New York Times critic Janet Maslin praised the film on its December 1987 opening in the city, noting that the skill with which it was made was “sure to be eclipsed in importance by the fact that it was made at all.”

The one place where the film did not break through quickly was in East Germany. It had been broadcast on West German television in October 1987 and widely seen by people in the Communist-controlled part of the country, where it was banned, but the damage had been done. East German viewers found clear similarities to their own oppressive regime in the film’s story, forcing the authorities and press there to begin a campaign to denounce a movie that officially its citizens could not even see.

Repentance won wide international acclaim, including three top prizes at Cannes (among them the Grand Prix), two at the Chicago International Film Festival, and a Golden Globe nomination as Best Foreign Language Film. In itself, these honors from the West were not nearly as remarkable as the film’s six wins (Best Film, Director, Actor, Cinematographer, Screenplay, and Production Designer) in the 1988 Nika Awards, the Soviet (and now Russian) equivalent of the Academy Awards. The scathing satire had been a phenomenon in its home country, one of the earliest signals of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Abuladze made only one other film, Khadzhi Murat (1989) before his death in 1994 at the age of 70.

Director: Tengiz Abuladze

Screenplay: Tengiz Abuladze, Nana Janelidze, Rezo Kveselava

Cinematography: Mikhail Agranovich

Editing: Guliko Omadze

Production Design: Giorgi Miqeladze

Original Music: Nana Janelidze

Cast: Avtandil Makharadze (Varlam/Abel), Iya Ninidze (Guliko), Zeinab Botsvadze (Ketevan), Ketevan Abuladze (Nino), Edisher Giorgobiani (Sandro)