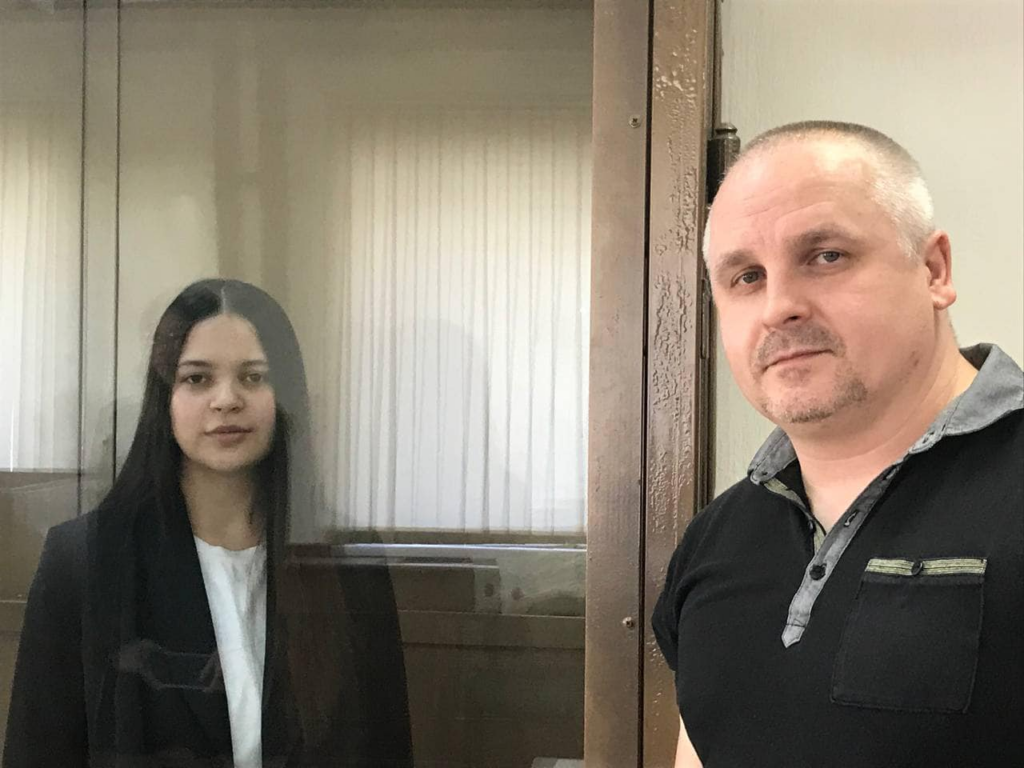

Leniye Umerova is a 25-year-old Crimean Tatar marketing specialist who has been held in Russia’s captivity since December 2022. She was detained on her way to occupied Crimea to see her father, who had been diagnosed with cancer. Russia wants to imprison her for 20 years.

Russia’s top propagandist, Olga Skabeeva, interrupted her talk show on May 16 to share “breaking news” with the Russian people.

The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) uncovered a spy, Skabeeva said, who had been feeding information about Russian military infrastructure and equipment to Ukrainian authorities.

“A (criminal) case was opened into espionage. The lady will be imprisoned for 20 years,” Skabeeva said.

The woman that she was referring to was Leniye Umerova, a 25-year-old Crimean Tatar marketing specialist who was born in Crimea, went to university in Kyiv, and sought refuge in Turkey after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

“She never had anything to do with the special services or armed forces,” her brother, Aziz Umerov, 28, told the Kyiv Independent.

“She is just a regular hipster girl.”

Last December, Umerova decided to travel to Russian-occupied Crimea to look after her father, who had been diagnosed with cancer. She had a long journey to Georgia, where she caught a bus to Sevastopol, Crimea’s largest city.

Umerova was detained at the Georgian-Russian border. She was the only passenger with a Ukrainian passport, according to her brother.

By the time Skabeeva, as well as multiple Russian government-controlled media, shared the “breaking news” story about Umerova’s capture, she in fact had been in Russian captivity for about five months.

Russia kept Umerova at detention facilities in the remote cities of Vladikavkaz and Beslan and then transferred her to Moscow, where she was charged with espionage.

Olha Skrypnyk, the head of the Crimean Human Rights Group, believes there are “clear signs” that Russia has fabricated the case against Umerova for political reasons: The fact that it took Russia five months to press charges against Umerova indicates that they needed this time to falsify the evidence against her.

To keep her under custody before pressing the trumped-up charges, Russia used methods that Umerova herself compared to those of the 1990s gangster movies.

“Intimidation, threats, abductions,” as she described what happened in one of her letters from Russian captivity.

“The only ‘crime’ and the reason for my sister’s imprisonment was her refusal to receive a Russian passport in 2014 (in Crimea),” her brother says.

Russia invaded and illegally annexed the Ukrainian peninsula in 2014, violently suppressing any resistance to its illegal regime. Throughout over nine years of occupation, Crimean Tatars, the indigenous people of the peninsula, have been the main target of Russia’s brutal repressions.

“Leniye Umerova tried to visit her sick father in occupied Crimea. Now Russia wants to sentence her to 20 years in prison,” President Volodymyr Zelensky said during the Crimean Platform summit in August.

“This is just one of the many examples of repression by the occupiers against Ukrainian citizens in Crimea, against the Crimean Tatar people, against the Muslim community of Crimea,” Zelensky said.

Home, taken

Umerova was 16 when Russia occupied Crimea.

She left the peninsula for Kyiv in 2015 to finish high school since she was told that she wouldn’t be able to graduate from high school in Crimea without first obtaining Russian citizenship.

By that time, her brother was already in Kyiv, where he had relocated to study in a university.

Their parents, however, chose to stay in Crimea.

“They said that they were born in exile in Central Asia and dedicated their whole lives to return to their land,” says Umerov.

“If, for us, the struggle began in 2014, and our lives had been relatively calm before that, our parents and grandparents have been going through it their whole lives.”

In 1944, the Soviet regime falsely accused the entire Crimean Tatar people of collaborating with Nazis. Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin soon ordered the deportation of all Crimean Tatars from the peninsula. They were allowed to return home only in the late 1980s.

“They (parents) simply could not give up their home to Russia, to our historical enemy, and decided to stay,” Umerov says.

With every year of occupation, cases of human rights violations in Crimea have grown.

As of February, there were 180 political prisoners in Russian-occupied Crimea, including 116 Crimean Tatars, according to Ukraine’s human rights ombudsman, Dmytro Lubinets.

Umerov says that in 2014, people could rally with Ukrainian flags, shouting “Crimea is Ukraine.” Now, he says, even liking some pro-Ukrainian posts on social media could lead to imprisonment.

He knew that traveling to Crimea during the full-scale invasion could be dangerous for his sister. And he tried to stop her.

“But she wanted to see her dad. She did not know when she would be able to see him again and if she ever would,” Umerov says.

’90s gangster series’

“I crossed off the days in the calendar today, and it turned out that soon it will be nine months that I’m being held here, in this country,” Umerova wrote in a letter from captivity in September.

“It seems that yesterday I tried to visit my father, but everything happened not as expected. A moment, and at the border, after checking documents and personal belongings, four unknown men approach you and force you to get off the bus and do everything as they say.”

Later, Umerova would tell her family that the “unknown men” were Russian FSB officers dressed in civilian clothes. They took her from the “Verkhniy Lars” checkpoint in North Ossetia to the police station in nearby Vladikavkaz.

They took her personal belongings and interrogated her for seven hours, she wrote.

That’s when the whole complex “scheme” to justify keeping Umerova under custody began.

“Late at night, they told her she had to go to some hotel they had already picked and continue the conversation with them in the morning,” Umerov says.

As Umerova was put in a taxi, she did not have to say the hotel’s address to the driver: He already knew where to take her. While driving in the countryside, a Russian traffic police stopped the taxi.

“They informed her that she was in the border zone, which foreigners were prohibited from entering without a special permit,” says Umerov. “So, they detained her.”

At around 3 a.m., she was brought to a local court that ruled to send her to a detention center for foreigners. She spent the next three months.

With the help of lawyers, hired by Umerova’s family, the court reversed the ruling.

In the middle of the night, Umerova was kicked out of the detention center without any means and permission to contact her relatives, who were on the way from Crimea to pick her up.

“As soon as she got out, a car with four men pulled up to her. They put a bag over her head, drove her to another part of Vladikavkaz, and kicked her out of the car,” Umerov says.

Lost, Umerova tried to look for help on the street when another police squad arrived.

“They issued her a report for malicious disobedience,” Umerov says. “The next day, the court arrested her for 15 days.”

During that time, Umerova was allowed to have brief phone calls with her parents, which Russia would later use to prolong her arrest.

“On the 13th day of her arrest, she was issued another protocol for disobedience, for allegedly not ending her (phone) conversation on time,” Umerov says.

Several more protocols for disobedience followed, according to Umerov. She was soon transferred to a detention facility in the nearby town of Beslan.

“There was complete falsification of everything just to keep her in custody while the criminal case against her was being falsified,” he says.

“I remember that on the first day in prison, during the search of my personal belongings, I thought how this whole thing reminded me of an action-packed gangster movie from the 1990s,” Umerova wrote in her letter.

“And the next five months showed that this is not a movie but a TV series.”

No justice

To have a chance to see their daughter in Beslan, Umerova’s parents rented an apartment right next to the facility she was kept in.

Their short meetings were recorded on camera, and they were allowed to speak Russian only, Umerov says.

However, one day in early May, as the parents came to see Umerova, they were told she was no longer there.

“They learned that the FSB officers came and took her in an unknown direction,” Umerov recalls.

Later, they would find out she was transferred to Moscow with the Lefortovo district court pressing espionage charges against her.

Then, Russian propaganda created the whole “FSB uncovered a Ukrainian spy” story without mentioning that Umerova had been illegally detained months ago.

Skrypnyk says that if Russia “had at least something to accuse Umerova of, they would have done it right away.”

The human rights activist expects that the Russian court will continue extending Umerova’s term in detention. During the last hearing in late September, she was ruled to stay under custody until Jan. 4, 2024.

Umerova is now kept at the Lefortovo pre-trial detention center, often described as Russia’s most “severe” prison.

Skrypnyk says that arresting Umerova is “yet another confirmation of the systemic nature of the persecution (of Crimean Tatars).”

“It also shows that Russia can make up a criminal case against anybody.”

In her letter from captivity, Umerova wrote that what happened to her is “gross evidence of contempt for human rights, freedoms, and dignity, which was formed as a result of someone’s aggressive ambitions and has become a terrible norm for almost 10 years.”

“And we, all together, root out the cause of this problem.”

by Daria Shulzhenko

@ Kyiv Post