Russia’s Unresolved Historical Traumas Have Now ‘Taken The Form Of War

February 01, 2023

By Andrei Arkhangelsky

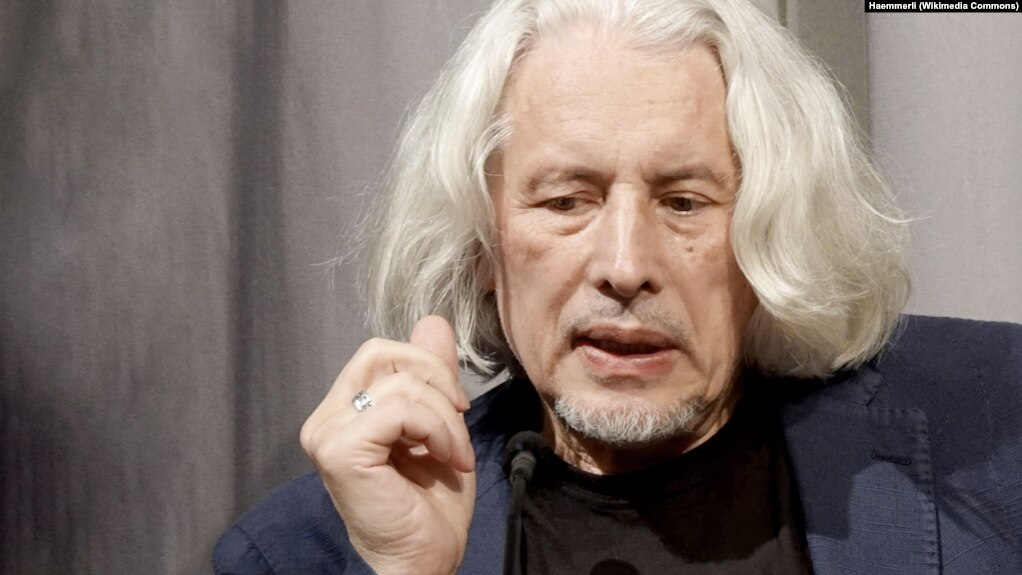

Vladimir Sorokin is among the best-known Russian authors of the last 50 years, a leading postmodernist whose works have been translated into dozens of languages. For years, the 67-year-old has divided his time between Germany and Moscow, although he has remained outside Russia since the Kremlin launched its large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

In the 1990s, he became known for his trenchant depiction of the traumas inflicted by the experience of Soviet totalitarianism. Poet Yelena Fanailova has said of him: “He hears underground water.”

It can’t be a coincidence that the main symbol of this insane war is the Latin letter Z for zombie.”

In 2002, he became one of the first targets of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s system when activists of the nationalist, pro-Putin Walking Together movement burned his books as allegedly pornographic.

His 2006 novel, The Day Of The Oprichnik, is a dystopia that depicts Russia in 2027 as a medieval dictatorship isolated from the world by a “Great Wall of Russia.”

Three days after the unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, Sorokin published a scathing indictment of Putin, who he said is the determined enemy of “Western civilization — the hatred for which he lapped up in the black milk he drank from the KGB’s teat.”

RFE/RL Russian Service contributor Andrei Arkhangelsky spoke with Sorokin about the war, the forces driving it, and its consequences for Russian society and culture.

RFE/RL: In your interviews, you describe the system of Russian President Vladimir Putin as “archaic” in the tradition of the medieval Tsar Ivan the Terrible. But maybe it is actually some unexpected, monstrous permutation of postmodernism?

Vladimir Sorokin: No, I still think it is archaic. It is stronger than postmodernism because the state machinery exists according to models constructed in the 16th century. The present “power vertical” does not significantly differ from the pyramid of power created by Ivan the Terrible. Of course, it isn’t made of brick and wood, but rather of glass and concrete.

But we are all to blame, of course — not just Putin and his team.

RFE/RL: You once said that the corpse of the Soviet world was not buried in the 1990s but rather continued to rot in the corner all these years. Now that corpse has stood up and started killing. How is that possible? What kind of creature is this?

All us Russians will have to drink from a bitter cup…. We are all to blame, of course — not just Putin and his team.”

Sorokin: A zombie. And, as zombies do, it came back to life, but not as a human. During the era of [Russian President Boris] Yeltsin, it was shoved into a corner and covered with sawdust. They hoped it would rot away on its own. But no. It turned out to be alive – in an infernal, otherworldly sense. It was brought back by champions of imperial resentment, both on television and in real life. They hooked it up to electrodes, and, to use an expression, the corpse got up off its knees. Now it is destroying foreign cities and threatening the world with nuclear weapons. It can’t be a coincidence that the main symbol of this insane war is the Latin letter Z for zombie.

In effect, we didn’t manage to bury this power pyramid of Ivan the Terrible back in the 1990s. It just took on a new façade and remained standing. But, as in the 16th century, there is one ruler at the top exercising total power. And below him there are the oprichniki (the notorious political police force created by Ivan the Terrible) and innumerable loyal serfs.

RFE/RL: The war in Ukraine has nullified the efforts of millions of our countrymen who wanted to live in a new way. All the efforts of the last 30 years — since Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika — have been in vain. It feels like our entire conscience existence has been for nothing. Don’t you feel this way?

Sorokin: Of course, that is an ontological question, but it wasn’t all in vain. If only because we are still alive, and we can talk about all this. There is a sufficient number of Russians with common sense who understand that the inertia of five centuries was too strong. It turned out that a small group of democrats in the 1990s was not able to stop this machine. Perhaps because they included many former communists. It wasn’t like in Germany in the late 1940s or in Czechoslovakia in the 1990s. We didn’t have a Vaclav Havel, unfortunately. Germany suffered complete military defeat, and the victors decided everything. They dug the grave for the corpse of Nazism, and German anti-fascists threw it in.

In the 1990s, most of the countries of the former Soviet bloc managed to bury totalitarianism. But the Soviet Union collapsed of its own unsustainability. I’m not talking about economic or political questions, but the basic necessities of life. I remember back in 1979, I was working at the magazine Smena. I had a colleague who lived in [the Moscow suburb of] Sergiyev Posad and rode a commuter train into work. He told me how one Saturday morning his little son woke up and said, “Papa, I’d like some smoked sausage.” So, what could he do? He got on the train and went to Moscow for some smoked sausage.

That was in 1979, just outside of Moscow. It wasn’t in 1949 or 1929. People were still traveling to Moscow from the provinces to buy women’s shoes or smoked sausage. Such a system is unsustainable, especially if is launching spaceships while not being able to provide basic essentials to its population. That is why it collapsed — not because of some machinations of the CIA. Not because it lost a war. That is why it came back to life. No one dug the grave of Soviet communism for us.

RFE/RL: Isn’t there in this war a bit of the Freudian idea of the unconscious death drive of the entire regime? The Putin system existed more or less fine for 22 years. People were living a little bit better than they did in Soviet times. But for some reason they needed to destroy everything, including themselves.

The Soviet man couldn’t even choose what cigarette to smoke….The state crushed the individual, and he lashed out at his relatives and neighbors…. We have a deeply traumatized society, and now this trauma has taken the form of war.”

Sorokin: This idea is going around, and a lot of people are talking about it. “They die, but we go to paradise” — this aphorism of Putin’s has now become state policy. But the first thing that was killed off was common sense. The stuff our officials are saying on television — to say nothing of what the propagandists spout — is beyond the realm of normal thinking. It is pure paranoid schizophrenia. I think psychiatrists and social anthropologists will be analyzing all this for years.

RFE/RL: Why do people go along with this mass suicide? Where does this collective loss of the basic self-preservation instinct come from?

Sorokin: I was a boy in the 1960s, and outwardly those were quite prosperous years. There were no mass repressions. People weren’t living in terror that someone would come in the night and take them away. But inside everyone there was a particle of this fear — and violence as well. It broke through occasionally — in the household, on the trains, in shops. After all, what is the essence of the Soviet project? It is not a crime against humanity but against humans as a species. A blow to each individual. Soviet man was forcibly deprived of all choices.

Inner freedom is, in fact, freedom of choice. That is the main characteristic of Homo sapiens. A person can choose to live or not. Animals cannot. But the Soviet man couldn’t even choose what cigarette to smoke. The stupid, unmotivated malice of people like Martin Alekseyevich (a character in Sorokin’s 1983 novel The Norm) is essentially the reaction of people to this lack of choice. I saw such ugliness as a child — in everyday life, in families, on the streets. It came out in everything. The state crushed the individual, and he lashed out at his relatives and neighbors…. We have a deeply traumatized society, and now this trauma has taken the form of war.

It always happens that literature is the first to bear responsibility for war, although it doesn’t kill anyone. Such a reaction is natural in wartime — once-beloved books become the language of the enemy.”

RFE/RL: The war has forced us to rethink our entire Russian culture. Much has been written about the guilt of Russian literature, which is seen as militaristic and imperial by nature.

Sorokin: I do not agree that Russian literature is militaristic. [Poets Aleksandr Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov] wrote in the first half of the 19th century when imperial bellicosity was the norm everywhere. But is there militarism in [Leo] Tolstoy? He hated war in general, condemned it as madness and contrary to human nature…. I’d exclude our three bearded men (Fyodor Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Anton Chekhov) from this list. And [Ivan] Turgenev, too. They are not militarists.

I remember seeing footage from Kyiv after the invasion showing a portrait of Pushkin in a garbage can. This is normal. Ukrainians have every right to feel this way. Pushkin is the image of the tsarist empire. But not Tolstoy or Turgenev.

RFE/RL: One Ukrainian intellectual who grew up on Russian literature told me he threw everything — including Bulat Okudzhava and Josef Brodsky — into the trash on February 24. He wanted to break his last link to the Russian world. To me, the saddest thing is that we can’t blame him.

Sorokin: We can’t, because he is right. Just as the French and the Dutch who threw German books into the garbage in the 1940s, saying, “Our children will never learn Hitler’s language,” were right. But the war ended, and Goethe and Thomas Mann are read today in France and Holland. They are studied in universities. It always happens that literature is the first to bear responsibility for war, although it doesn’t kill anyone. Such a reaction is natural in wartime — once-beloved books become the language of the enemy.

RFE/RL: Here’s an unpleasant question: Are Russians collectively or individually responsible? Are we all responsible for the war?

Sorokin: Yes, I think both. Undoubtedly, as a Russian, I share the collective responsibility for the unleashed war. But I also have to ask myself what it was specifically that I didn’t do to prevent it. So it is for every normal person, I think. And this guilt is going to grow.

All us Russians will have to drink from a bitter cup. Everyone will have to carry a stone upon their backs — how big and how heavy is for each person to decide for themselves. But we are all to blame, of course — not just Putin and his team. As in the Stalin years, the regime relied on the fact that there are millions of people like Stalin and Putin — with the same consciousness, the same ethics, the same vocabulary.

Translated by RFE/RL correspondent Robert Coalson.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.