Many men wish death upon Serhii Sternenko. Four times in seven years assassins have tried to take the life of the Ukrainian social influencer and drone supplier whose outspoken views on war, culture and governance have earned him a following of millions in his country — and enemies near and far.

During one assassination attempt, Sternenko overpowered and detained an attacker who had tried to shoot him. Another time, he fought off and then fatally stabbed an assailant in Odesa.

The last person who tried to kill him was a woman. On May 1 this year, as Sternenko stepped from his rented flat in Kyiv accompanied by two bodyguards, Liudmyla Chymerska, 45, probably under orders from the Russian FSB, used a 9mm Makarov pistol to fire at least three bullets at him.

One bullet passed through the YouTuber’s thigh, leaving a gaping exit wound. Another went through a bodyguard’s shirt. As Sternenko was rushed from the scene in an armoured Range Rover, he applied a tourniquet to his thigh to stop the bleeding, then checked his pulse. It ran at 126 beats per minute: a little faster than the ideal bracket, but not bad for a gunshot casualty.

“‘Not today’, as we say to the god of death,” he smiled, leaning across his desk to display a patch embroidered with death’s skeletal hand being severed by an arrow.

Nationalist, activist, streetfighter, social influencer, lawyer, YouTuber and one of the main non-state suppliers of first-person view (FPV) suicide drones to the Ukrainian army, Sternenko has become the best-known military blogger in Ukraine, an influential voice with more than two million subscribers on the video-sharing site and a further 852,000 followers on Telegram.

“After the full-scale invasion began here, I knew the Russians would try to kill well-known Ukrainians,” he said. “I knew sooner or later they would come for me. If I was in their position, I would do the same.”

Loathed by the Russians, the 30-year-old from Odesa oblast is also regularly in trouble with the Ukrainian establishment over his repeated denunciations of the corruption that plagues so many of the country’s institutions. Other critics have accused him of avoiding the military draft — a charge he denies.

Yet, among Ukraine’s younger generation of soldiers and civilians, Sternenko’s brand of truth to power has wide popularity. “I say what I think, and people like what I say.”

His views on President Putin’s demand for Ukraine to cede the territory it defends in the eastern Donbas region as a precondition for possible peace are typically direct. “If [President] Zelensky were to give any unconquered land away, he would be a corpse — politically, and then for real,” Sternenko said. “It would be a bomb under our sovereignty. People would never accept it.”

Indeed, as he discussed Russian intransigence and President Trump’s efforts to end the war, Sternenko’s thoughts on the possibility of peace appeared to be absent of any compromise over Ukrainian soil.

“At the end there will only be one victor, Russia or Ukraine,” he said. “If the Russian empire continues to exist in this present form then it will always want to expand. Compromise is impossible. The struggle will be eternal until the moment Russia leaves Ukrainian land.”

Russia’s intelligence services have many reasons to want Sternenko dead. Primarily, however, it is the FPV drones he supplies to the Ukrainian army, which kill more Russian troops than any other weapon, that has secured him a place on the FSB hit-list.

Since 2022, the blogger’s campaigns have raised nearly 5 billion hryvnia (£90 million): enough to supply 216,532 drones to Ukraine. This year alone his fundraising platform, the Sternenko Community Foundation, has received more than 1.5 billion hryvnia.

Present at many of Ukraine’s key events from the start of the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, Sternenko’s journey to prominence, paved by political violence and deep controversy, mirrors in part the passage of Ukraine.

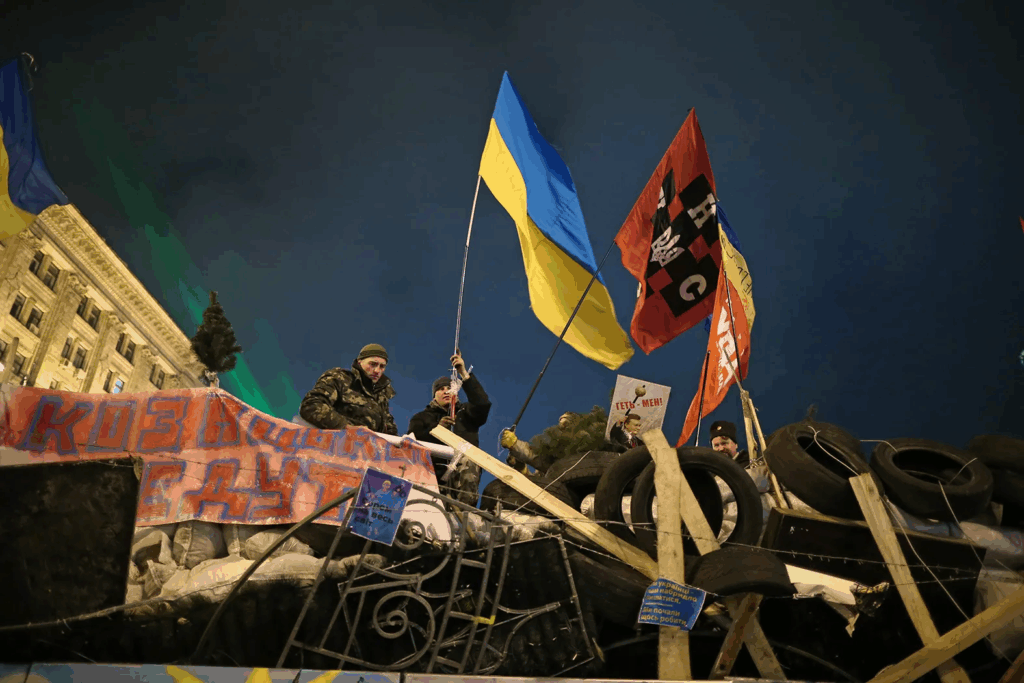

Political activists, civil society groups and students first began to protest against the pro-Kremlin President Yanukovych in Kyiv’s Maidan Square in 2013, angered by their leader’s rejection of an Association Agreement proposal with Europe and his government’s abuses of power. The protests spread across the country and intensified as police violence increased against the demonstrators.

In February 2014, 108 protesters and 13 police officers were killed in a series of clashes around the barricades in Maidan Square. Most of the deaths occurred between February 18-20, when police snipers opened fire on thousands of protesters advancing on parliament.

On February 21, Yanukovych fled. Russian troops occupied Crimea the following month. By April, pro-Russian separatists began seizing areas of the Donbas. In one form or another, war in Ukraine has continued ever since.

Sternenko, then aged 18, was present for the worst of the Maidan violence. A photograph shows him masked, helmeted and confident against a backdrop of smoke and shielded men along darkened barricades at the peak of the streetfighting. It was a defining moment.

“I saw people killed and wounded around me,” he recalled. “Though I didn’t feel afraid at the time, in the days afterwards I realised it could be me lying in a coffin.

“Such moments change your awareness of life. I am aware of a certain finite time here, in which I have to do something useful for my people and my country.”

Yet, soon afterwards, Sternenko became embroiled in more political violence, this time in Odesa, and there was a bitter aftermath.

The port city, infamous for its corruption and organised crime groups with links to Moscow, had become the focus of a violent struggle between Maidan supporters and pro-Russian elements. Clashes in the streets turned bloody and on May 2, 2014, rival protesters fought with petrol bombs and gunfire. The pro-Russians were driven back into Odesa’s Trade Unions House. Both sides hurled petrol bombs and the building caught fire. Forty-two people died in the blaze, most of them pro-Russians.

Sternenko, who two months earlier had been appointed head of the Odesa branch of the Right Sector, a coalition of right-wing and far-right Ukrainian nationalist groups, was on the streets for much of the day’s violence. “As soon as I saw a pro-Russian being beaten on the ground, I ordered it to stop,” he said. “And I gave orders for the people inside the building to be rescued.”

However, the Odesa fire was a dark moment. In the aftermath of the blaze the pro-Maidan protesters were accused by Russians and pro-Russians of causing a deliberate massacre, and Right Sector members were regularly described as Nazis.

Sternenko remained at the forefront of protests in Odesa over the following years, representative of the antipathy felt by an emerging younger generation of Ukrainians towards their elders working in local authorities, many with pro-Russian sentiments. “The main aim of that time was to release Odesa from corruption schemes and pro-Russian influence,” he said.

Although he has left Right Sector and is unaffiliated with any party — “I dislike them all equally” — Sternenko gave a carefully calibrated response when asked whether he was still a nationalist. “Do I think Ukrainians should be more aware of their culture and history? I do. I would like my nation to understand itself and become more aware, so people can prosper on their own land free of Russian subjugation. In those terms, I am a nationalist.”

With a growing list of enemies, Sternenko’s next controversy occurred in May 2018, when he was attacked one night by two men outside his flat in Odesa on returning home with an armful of groceries. In the struggle, Sternenko fatally stabbed one of his attackers; the other assailant fled.

The killing plagued Sternenko in the following five years, as prosecutors in Odesa sought to challenge his claim of self-defence with a charge of excessive force and premeditated murder. Sternenko countered that he was the victim of the attack, and claimed that he was being hounded for political reasons by a corrupt pro-Russian judiciary. The Odesa court finally closed the case against him in December 2023. “They even returned my knife to me,” he said.

Although the experience was at times bruising, Sternenko’s fanbase soared and now the case is closed, he may find that he has the chance of revenge. Learning that Alexander Isaikul, the surviving attacker, who escaped that night, is in Russia and may have been mobilised by the army, Sternenko wonders whether one of his FPV drones could down him. “I would like to see him in one of my drone screenshots,” he smiled.

Looking back, Sternenko sees that the most recent attempt to kill him came as part of a chain of assassination attempts by the FSB in Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion.

Iryna Farion, a Ukrainian linguist and ultra-nationalist, was assassinated in Lviv in July last year, shot in the head outside her home. Then, in March this year, Demyan Hanul, a friend of Sternenko’s and a fellow activist, was shot dead in Odesa. Sternenko had already been warned by the Ukrainian intelligence service that the Russians were planning to assassinate him. He was almost expecting it when Chymerska shot him.

“Once Demyan had been killed, I knew that they would be close and coming for me next,” he reflected. “The Russians wanted to have that day as a day of revenge.”

Since her arrest, Chymerska’s accounts to investigators have varied. Already on dialysis for a kidney complaint, at first the failed assassin said that she had been persuaded to attempt the killing by a man with whom she had fallen in love. She said he groomed her on Viber, the messaging app, and told her Sternenko was a Russian agent who deserved to die. She appears to have now acknowledged FSB involvement in her orders, and mentioned that the Russian intelligence service had promised her a new kidney if she pulled off the killing.

As Sternenko lay recovering from the shooting in a hospital bed, where he received a call of support from Zelensky, his followers were quick to retaliate. Within 24 hours, publicity around the attack resulted in Sternenko’s drone fund receiving $500,000 to buy kamikaze drones to kill Russian troops. “Revenge for revenge,” Sternenko said.

It is unlikely to be the last time an assassin tries to kill him. In some ways, Sternenko finds the realisation refreshing. “If the enemy of my country is trying to kill me,” he mused, “then I know that I am doing something right.”