ERIC DAVID

SEPTEMBER 12, 2007

Russian filmmaker sought to harrow the soul

Raised in the Russian Orthodox tradition, director Andrei Tarkovsky once told an interviewer, “I consider myself a person of faith, but I do not want to delve into the nuances and problems of my situation, for it is not so straightforward, not so simple, and not so unambiguous.”

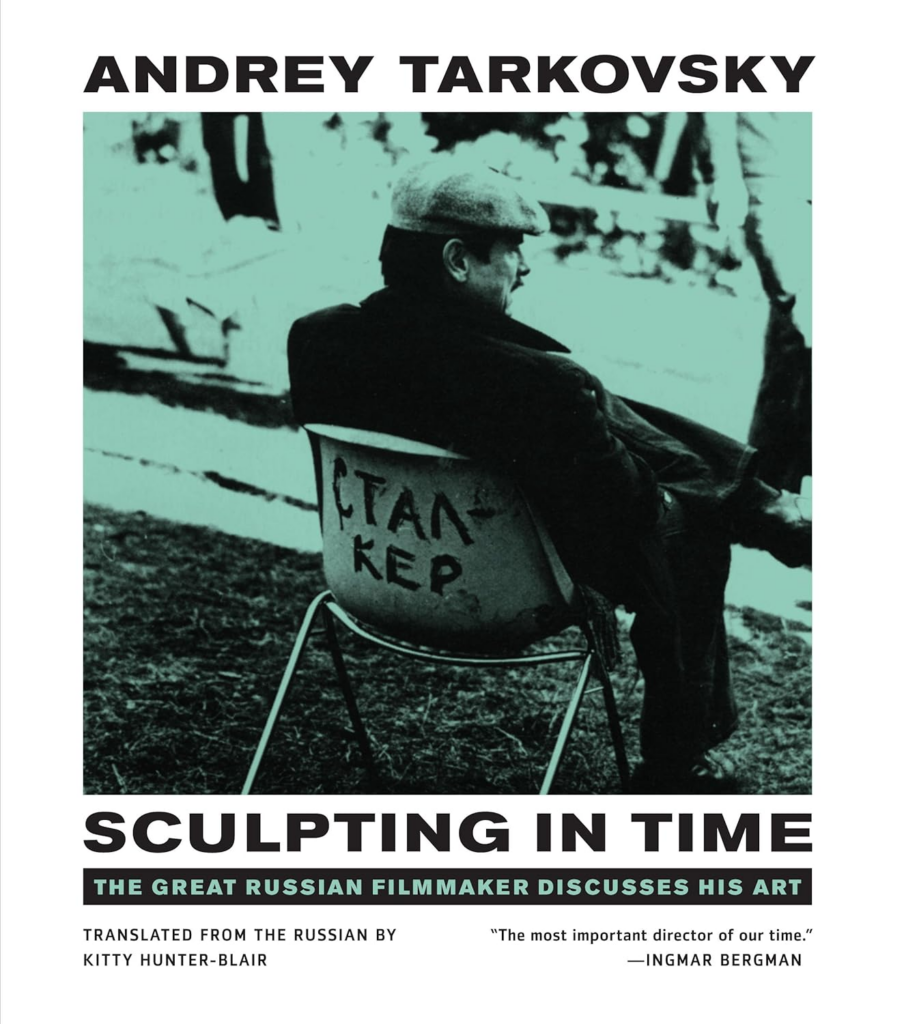

Obsessed with time, Tarkovsky often wrote about it. He thought film’s greatest quality as an art form was its ability to capture time and the director’s ability to “sculpt in time.” He thus compared motion pictures to the art form least involving motion.

Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time stands with Robert Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematographer as one of the best books on filmmaking written by a director. It delves deeply into the spirituality of the filmmaker: “Art should be there to remind man that he is a spiritual being, that he is part of an infinitely larger spirit to which he will return in the end.”

All of Tarkovsky’s films deal with apocalyptic scenarios. He once said, “It would be wrong to consider that the Book of Revelation only contains within itself a concept of punishment, of retribution; it seems to me that what it contains above all is hope.”

Ivan’s Childhood, about a boy living in wartime, was his first feature film and was championed by Jean-Paul Sartre. But with his next film, Tarkovsky became known as one of the great filmmakers. Andrey Rublev—originally titled The Passion According to Andrey—portrays the great Russian icon painter’s life during a period of enforced muteness.

“The aim of art is to prepare a person for death,” Tarkovsky, who died in 1986, wrote in Sculpting in Time, “to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good. … Art must transcend as well as observe; its role is to bring spiritual vision to bear on reality.”

Eric David, CT Movies reviewer

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today